14 Best British Screenplays to Download

We had a lively debate in the Kinolime offices the other day. In the wake of 28 Years Later dividing the public, opinions flew about whether Alex Garland and Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later is a British cinema masterpiece – or just a rip off of Day of the Triffids and Resident Evil. There were solid arguments on both sides. I’m staying out of it.

But it did leave me wondering: what is the greatest available British screenplay? The UK has a remarkable cinematic legacy – second only to Hollywood, in my view. So which screenplays are most worth reading, and what can they teach us?

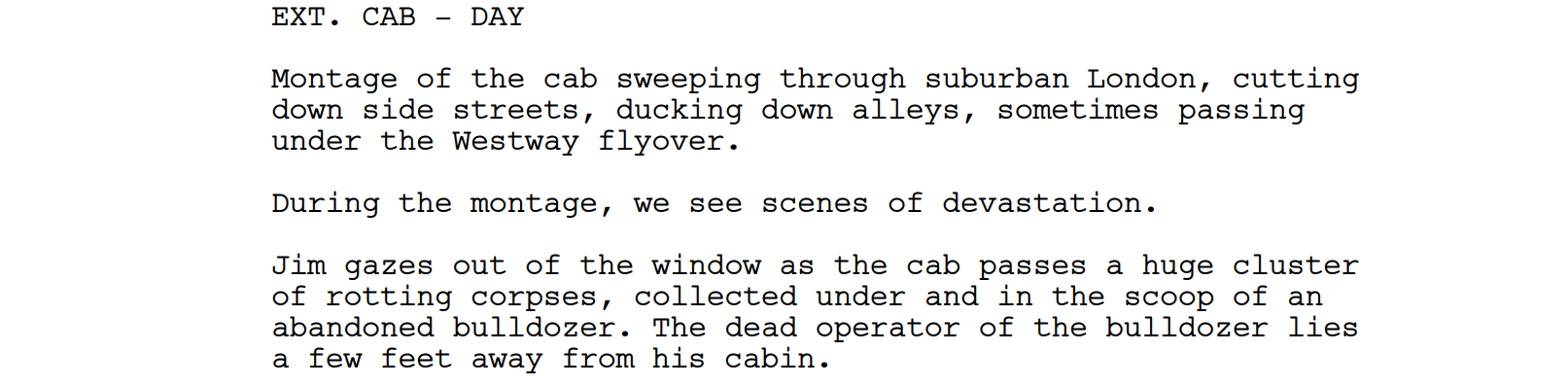

28 Days Later (2002)

Directed by Danny Boyle and written by Alex Garland, 28 Days Later is a cornerstone of modern British horror. It’s unmistakably British – funded in part by the UK Film Council, filmed across the UK, and starring a mostly British cast (Cillian Murphy’s Irish, before anyone gets upset). It did incredibly well, grossing $80 million worldwide on a modest $8 million budget.

It’s notable for revitalizing the zombie genre, popularizing the now-standard sprinting zombies and influencing everything from The Walking Dead to World War Z. But beyond horror, it captured early 2000s anxieties and a distinctly British sense of disillusionment, with a hauntingly empty London that became instantly iconic. Its gritty digital aesthetic and moral complexity gave it a realism rarely seen in genre films, and the impact firmly established Boyle and Garland as major forces in British and global cinema.

Perhaps its greatest attribute is its minimalism, use of silence and negative space, and ability to turn the recognizable or mundane into frightening sites of immediacy, violence, and peril. Whether or not you’ve lived in London – a taxi cab, empty streets, tunnels, service stations – these are everyday sights. Transforming the unexceptional into sources of fear is a powerful way to unsettle the viewer and make horror feel uncomfortably close to home.

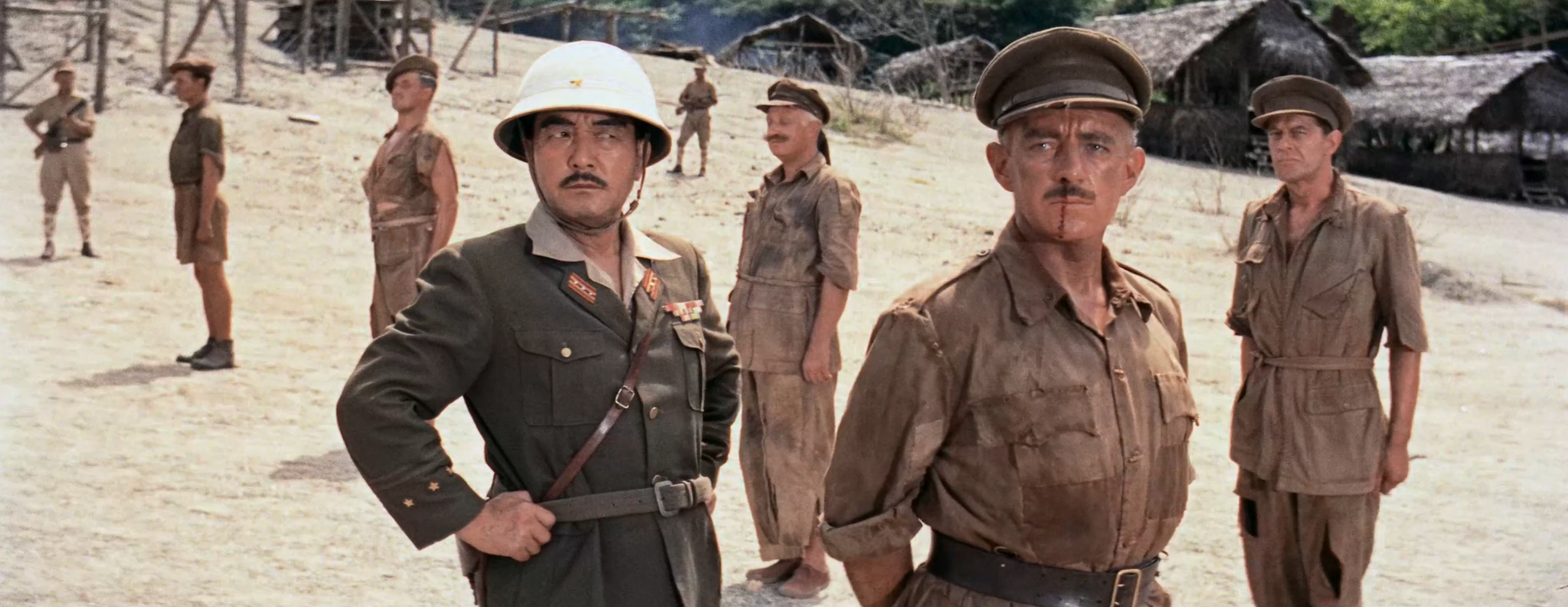

The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

Is there anything more British than a film based on a French novel, written by Americans, shot in modern-day Sri Lanka, and set in Thailand? The Bridge on the River Kwai is one of my all-time favorites – permanently cemented in my Letterboxd top four. Written by Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson (adapting Pierre Boulle’s novel), it’s a seminal, often underrated British war epic.

With a cast of British acting royalty led by Alec Guinness, the story follows British POWs in a Japanese labor camp, as they are forced to build a railway bridge. The screenplay reshaped the genre and became the blueprint for a war epic. It wasn’t without controversy – its portrayal of British stoicism and military honor is morally ambiguous, making it a patriotic, yet psychologically reflective milestone.

The film won seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Writers Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, blacklisted by Hollywood during the McCarthy era for suspected communist ties, adapted the novel in secret after fleeing America. They were finally recognized with posthumous Oscars for Best Adapted Screenplay in 1984.

What I love most about the screenplay is its slow-building, almost suffocating urgency. Even during long stretches – treks through the jungle, meticulous bridge construction, philosophical back-and-forths – time marches forward, unyielding. It’s also worth noting the available screenplay is an early draft, diverging more from Boulle’s novel than the final film, with scenes that were never shot or ended up on the cutting room floor.

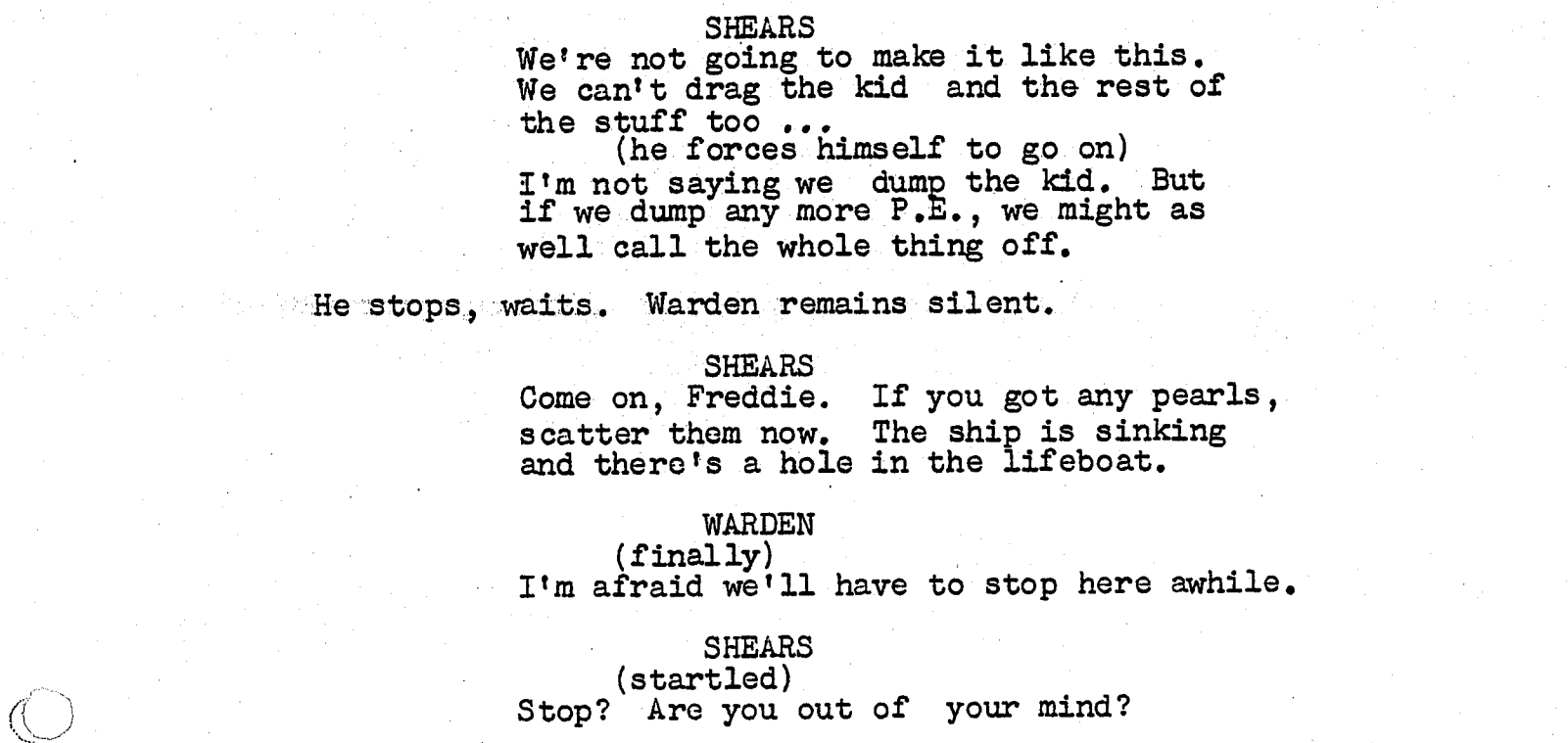

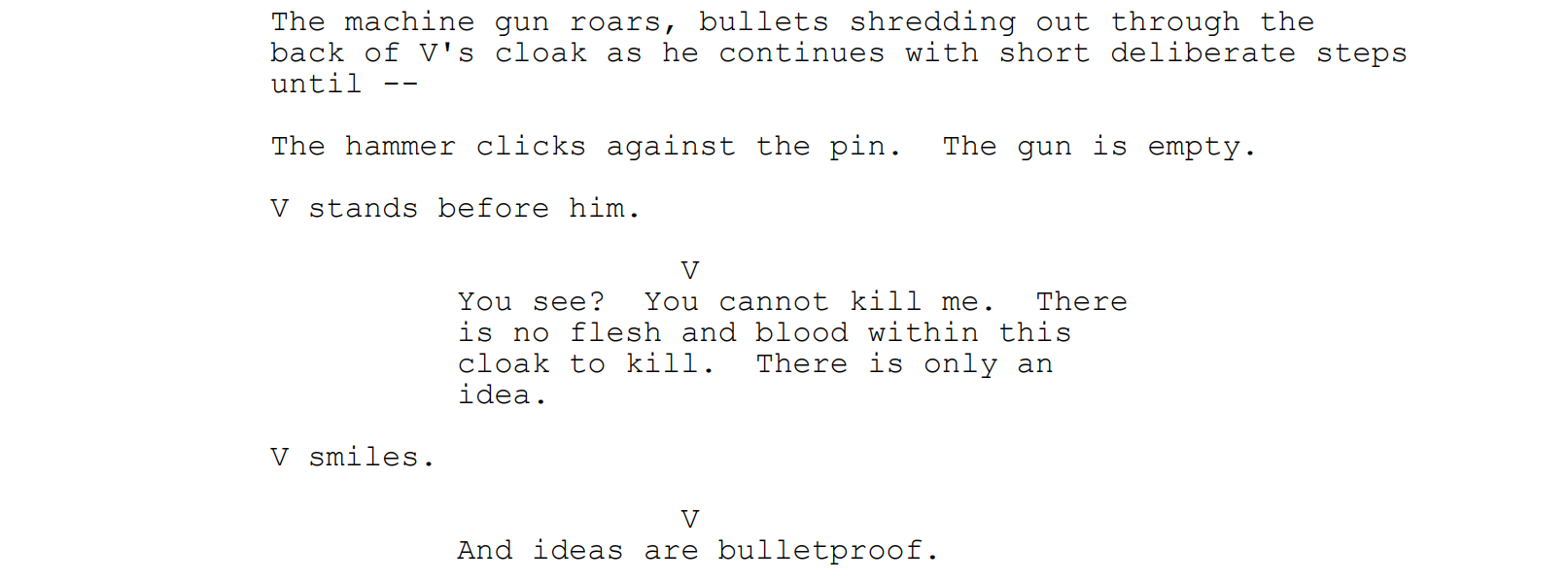

V for Vendetta (2005)

Switching gears – let’s talk about the sleeper hit that taught us Natalie Portman just can’t pull off a British accent.

V for Vendetta saw the Wachowskis adapted Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s graphic novel of the same name. Coming off the massive success of The Matrix trilogy, they turned to a story deeply tied to British identity and politics. Though critics were divided at release, it’s since become a cult classic – especially for its sharp political commentary. Its dystopian vision of a fascist Britain and the iconic Guy Fawkes mask have become worldwide symbols of protest and resistance.

Moore’s cinematic graphic novel combined with the Wachowskis’ flair creates a tense conspiracy filled with sharp one-liners and a literally explosive finale. Satire and social commentary are some of the most difficult aspects to write well, and the Wachowskis perfectly balance the scathing, the whimsical, and the ridiculous. V for Vendetta remains one of the most enduring politically charged British films of the 21st century – provocative, stylized, and strikingly relevant today.

Trainspotting (1996)

Here’s another Danny Boyle entry – and I’m going to be a little controversial here in admitting I’m not a massive fan of this film. That being said, no one can deny the excellence of John Hodge’s screenplay adaptation of Irvine Welsh’s novel.

Trainspotting is a defining film of 1990s British cinema. Set in Edinburgh, it stars a now-iconic Scottish cast, including Ewan McGregor and Robert Carlyle. This unflinching look at heroin addiction became a global phenomenon, earning over $70 million worldwide.

The available screenplay is oddly formatted but worth reading as an adaptation study. Hodge captures the dialect-heavy novel’s core, softening the rough edges while keeping its sharp, edgy tone. It’s packed with bleak humor, emotional rawness, and an anti-establishment vibe. I also love how it balances dark moments with surrealism and deadpan wit.

Children of Men (2006)

Children of Men, directed by Alfonso Cuarón and based on British author P.D. James’s novel, is a modern dystopian sci-fi classic. Often hailed as one of the best British films of the 21st century, it offers a poignant, prophetic vision of a bleak near-future Britain and a thoughtful take on apocalypse. In this world where humanity can no longer reproduce, a group rallies to protect the world’s only pregnant woman from desperate forces eager to exploit her unborn child’s potential.

What I love about this immersive screenplay is how it demonstrates how everything can be politicized when there’s something to capitalize upon. Whether you want it or not, everything is inherently political – and the opportunity to claim otherwise is a privilege afforded to very few.

Though not a major commercial hit at first, its reputation has steadily grown. Critically, it earned three Oscar nominations for its bold direction. Culturally, Children of Men is now seen as eerily prophetic, reflecting anxieties about immigration, authoritarianism, and societal collapse.

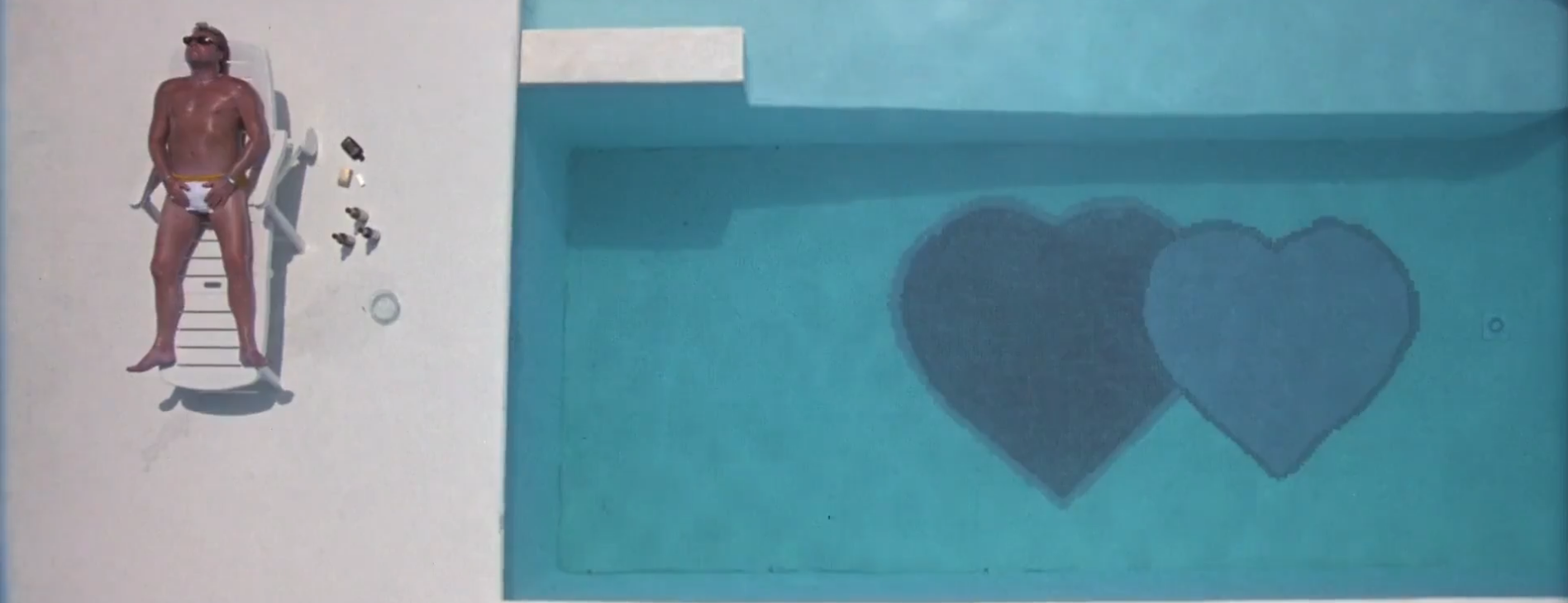

Sexy Beast (2000)

Sexy Beast is a quintessential British crime drama, directed by Jonathan Glazer and written by Louis Mellis and David Scinto. A fully British production – filmed in Spain and London – it boasts a standout British cast, including Ray Winstone, Ian McShane, and Ben Kingsley (who plays very against type). Kingsley earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor, a rare achievement for such a profane role.

The rambling, expletive-filled insults and banter are pure Cockney, and you can tell Mellis and Scinto had fun writing it. Culturally, Sexy Beast revived the British gangster film, paving the way for Guy Ritchie’s success. It flipped the genre by focusing on a criminal trying to stay retired instead of climbing the ranks. Today, it’s seen as one of the most stylish and original British crime films of its time.

Aftersun (2022)

Aftersun (2022), written and directed by Charlotte Wells, is a deeply personal British drama that quietly captured critics and audiences alike. You’ve got to check out this screenplay for its tender, understated storytelling and emotional depth, focusing on a father-daughter bond during a holiday tinged with loss and depression. I especially love how the screenplay feels like a hazy memory, set in a time when moments stretch endlessly – like a sun-faded photograph.

While it’s one of the more contemporary pictures on this list, Aftersun is being hailed as a modern classic of subtle, character-driven storytelling. The film blazed through the UK arthouse circuit, was acquired by Mubi, won awards at Sundance and earned an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay.

Chariots of Fire (1981)

Chariots of Fire, directed by Hugh Hudson and written by Colin Welland, is a British cinema landmark. This modest British film about Olympic runners became an unexpected international hit, winning four Academy Awards – including Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay.

I’m always struck by the scene where Scotsman Eric Liddell refuses the Prince of Wales’ request to run his Olympic heat on a Sunday, breaching his religious values. It’s a powerful moment that pulls the audience both ways – we want Liddell to succeed, but to do so would be to erode everything he knows about himself.

Culturally, Chariots of Fire became a symbol of British pride and perseverance, touching on faith, identity, and quiet resistance. It sparked renewed interest in British period dramas and showed that homegrown, character-driven stories could resonate globally. Its influence still echoes in British film and sports storytelling – and no beach run feels complete without Vangelis’ iconic score.

Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994)

Four Weddings and a Funeral, directed by Mike Newell and written by Richard Curtis, is a British romantic comedy that catapulted the genre – and a foppish Hugh Grant – onto the global stage.

Of all the screenplays on this list, this is one of the most painfully British (I say complementarity) – dry wit, class consciousness, adherence to tradition, melancholic undercurrent – it has about every British hallmark available. Check this one out for Curtis’s witty, warm writing which balances humor and heartbreak. It’s an accurate but exaggerated portrayal of 90s British relationships and class dynamics.

Internationally, it grossed over $240 million worldwide, a staggering success for a film with a modest budget of around $3 million. It received nominations – Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay – and helped spark a global appetite for British rom-coms. Its cultural legacy is undeniable, laying the groundwork for Curtis’s later hits like Notting Hill and Love Actually.

The Iron Lady (2011)

Let’s look at The Iron Lady (2011), directed by Phyllida Lloyd and written by Abi Morgan, is a British biographical drama centered on Margaret Thatcher, the UK’s first female (and most divisive) Prime Minister.

Morgan hails from Wales, a region of the UK deeply affected by Thatcher’s leadership. You might expect a scathing biopic, but Morgan shows ambitious restraint, blending Thatcher’s rise with a tender portrayal of her late-life dementia. Some find the screenplay cautious for avoiding major controversies, but I think it reignited debate about her legacy. I’d always rather a film is the impetus of a conversation rather than the conclusion.

In the wake of the success of The King’s Speech just a year prior, these films showcased the heights of performance-driven British biopics with the world. Internationally, it grossed more than $115 million worldwide, buoyed by global curiosity in the controversial figure.

Pride (2014)

We’ve got a fascinating opportunity here to investigate another Wales-centric screenplay; Pride is the inverse of The Iron Lady, showing the other side of Thatcher’s union-busting from the perspective of the downtrodden.

Written by Stephen Beresford, Pride is a beloved British dramedy based on a true story of solidarity between LGBTQ+ activists and striking miners in 1984 Wales. The film performed well for a socially conscious indie picture, earning over $12 million worldwide.

Check this one out for its rousing sense of camaraderie, uplifting moments, and tasteful handling of delicate subject matter. I’m particularly fond of the joyous dance sequence, juxtaposing the traditional miners’ attitude with the ‘outrageous’ disco dancing of the era. Culturally, Pride became a touchstone for British queer cinema and political films, winning a BAFTA for Outstanding British Film, and remains another key example of British cinema’s ability to address activism with wit.

Atonement (2007)

Atonement (2007), adapted by Christopher Hampton from Ian McEwan’s acclaimed novel, is a sweeping British romantic period drama about truth, guilt, and the power of storytelling. Set against the advent of war, this is a story about the transformative nature of lies and naivety.

I implore you to read this one – especially if you’re going in blind. This is a lyrical, nuanced triumph. Light on dialogue, heavy on atmosphere, and demonstrating an incredible Rashomon-style repeating of events from different perspectives. This non-linear, unreliable narrator technique reinforces the film’s themes: subjectivity, memory, and the unreliability of narrative. Nettle’s speech about the British empire is especially poignant.

The film was a commercial and critical success, grossing more than $130 million worldwide. It received a nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Saltburn (2023)

Maybe a controversial inclusion, writer and director Emerald Fennell is an American, Barry Keoghan is Irish, Jacob Elordi is Australian – yet the production (BBC and A24 UK), the location, handling of British class warfare, and supporting cast are as British as a warm pint of ale.

Not my favorite screenplay, but I thought it was a worthwhile inclusion; the film gained recognition for its genre-bending dark humor, and post-modern examination of British class disparity. It’s included because it shows that not all British film is contemplative, the nation is producing edgier, controversial screenplays with complex characters and biting satire.

Though we’re not always certain what Oliver’s objective is, watching the gears turn in the minds of others as he manipulates them is always satisfying. There are several evocative scenes designed to shock – and let me tell you – they do their job.

Billy Elliot (2000)

Another personal favorite of mine; Billy Elliot is one of the quintessential Northern English films along with Kes and Wallace and Gromit. Set in the under-serviced and decaying County Durham, it tells the story of a young boy from a mining town who discovers a passion for ballet amid the 1984/85 miners’ strike. Have you noticed a pattern yet?

This is a special screenplay with a heartfelt and authentic portrayal of working-class life. Character development is exceptional, with Billy and his father reinventing themselves multiple times as they face the daily trials that life presents them. It’s bleak, it’s uplifting, it’s a cultural touchstone of British cinema. Mrs. Wilkinson is a delight of a character, the type of rigid hard-ass that is fun to write and slowly wear down.

Internationally, it earned over $40 million worldwide, earning a nomination for Best Original Screenplay at the BAFTAs and Oscars, and inspiring a hugely successful stage musical.

Conclusion

Now before I entertain any complaints – chances are I’ve snubbed your favorite screenplay. As sacrilegious as this omission may seem, I want to emphasise that we can only use screenplays that are publicly available. I’m not about to start using transcripts or assuming a script is great based on a strong film. I also attempt to include a range of eras, genres, and account for varying tastes.

There’s no Hitchcock in here, for instance. Starting with 1940’s Rebecca, Hitchcock’s work was American – written and produced in the USA, lacking British stars, locations, or subject matter. Prior to that, his best work is likely 1935’s The 39 Steps, for which no screenplay is available.

My major finding is that British cinema excels at adapting classic literature for the big screen, with many hits matching or surpassing their source material in the public consciousness. Screenplays reign supreme in the quiet melancholy of everyday people.

You’ve probably heard that art imitates life, and this seems especially pertinent for British filmmaking. I’ve noted that these screenplays can, by and large, be broken into two eras. From 1939 to 1980, we were focused heavily on World War II, obviously a major, defining influence on British art and identity. After 1980, there was a shift toward fear of fascism, sparked by the Thatcher era. Autocracy and dystopia became common themes, succeeding the WWII focus.

Even films outside these categories often serve as escapism from the fears affecting filmmakers and British audiences alike.

There’s a bright and evolving future for British screenplays, but this is a great place to get you started!