Alien (1979) Analysis– The Ultimate Spec Script

The Alien franchise, much like the titular Xenomorph, refuses to die. Disney+’s Alien: Earth has earned near-universal acclaim, with Roger Ebert even likening it to Andor – high praise for any series. This momentum follows Alien: Romulus (2024), widely seen as a return to form after the divisive Prometheus and Covenant. But today, we’re returning to the larval stage – the 1979 release that started it all.

It’s remarkable that this behemoth sci-fi franchise started as a humble spec script. And with spec sales climbing for the second year in a row, there’s no better moment to revisit a script that wasn’t just purchased, but spawned nine sequels and one of cinema’s most influential antagonists.

Unlike the script we’re about to dive into, I won’t keep you in suspense – this is a five-star screenplay. From the first page, with its smudged typewritten font, clipped “haiku-style” prose, and gritty retro-futurism, you’re instantly pulled into deep space with the crew of the Nostromo.

And then there’s the mythology of it all. Look at the title page; a screenplay based on a screenplay? Alien began as Star Beast, a Dan O’Bannon spec. Once Brandywine Productions picked it up, Walter Hill and David Giler came in for significant rewrites, most famously adding Ash (and his synthetic twist) and ‘the Company’ (later revealed as Weyland-Yutani). Those changes became cornerstones of the franchise’s lore. Despite their contributions, the WGA ultimately solely credited O’Bannon, much to Hill and Giler’s chagrin.

OPENING IMAGE

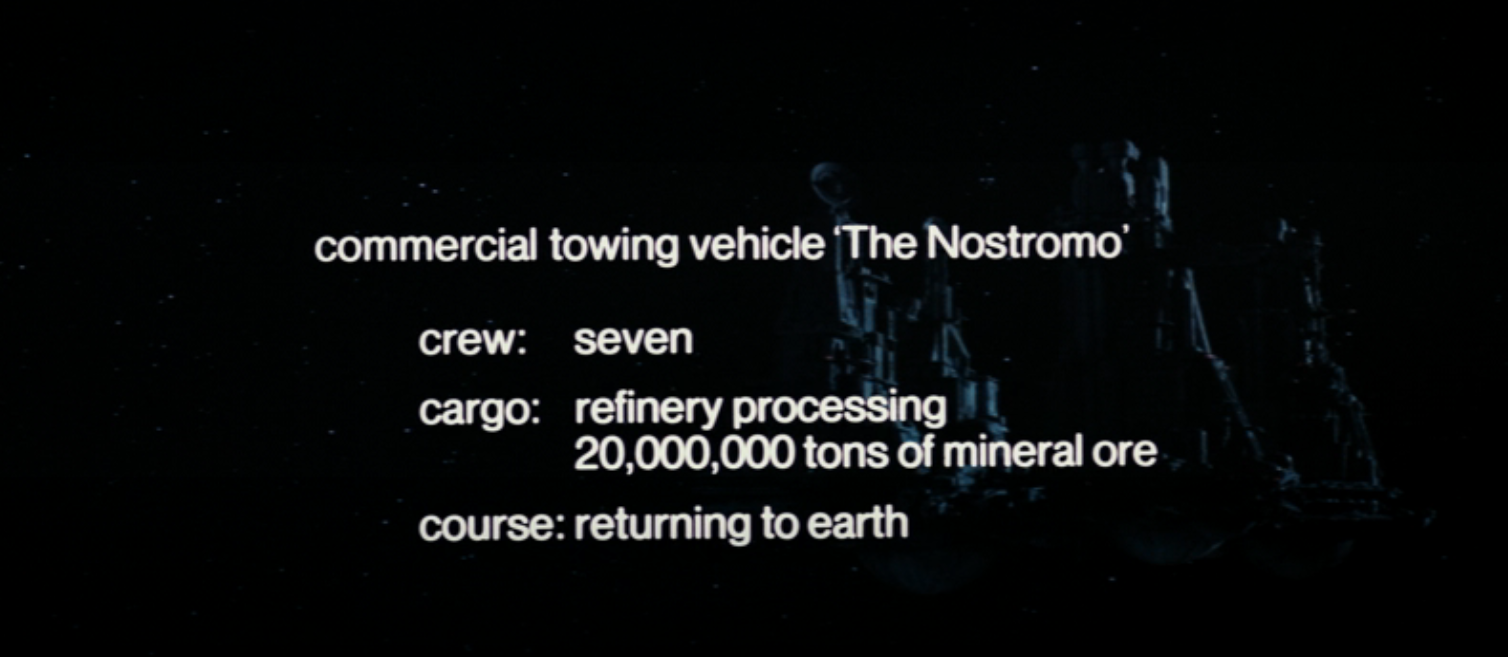

After the iconic title card floats over the cold vacuum of space, the Nostromo appears in the distance – a tug ship hauling a massive refinery cargo, so enormous it feels like a flying city. We’re left with more questions than answers – chiefly, how do seven people even run a ship this gigantic? It quickly sets the thematic foundation: corporate greed, overworked crews cutting corners, and the slow erosion of ethics.

SET UP

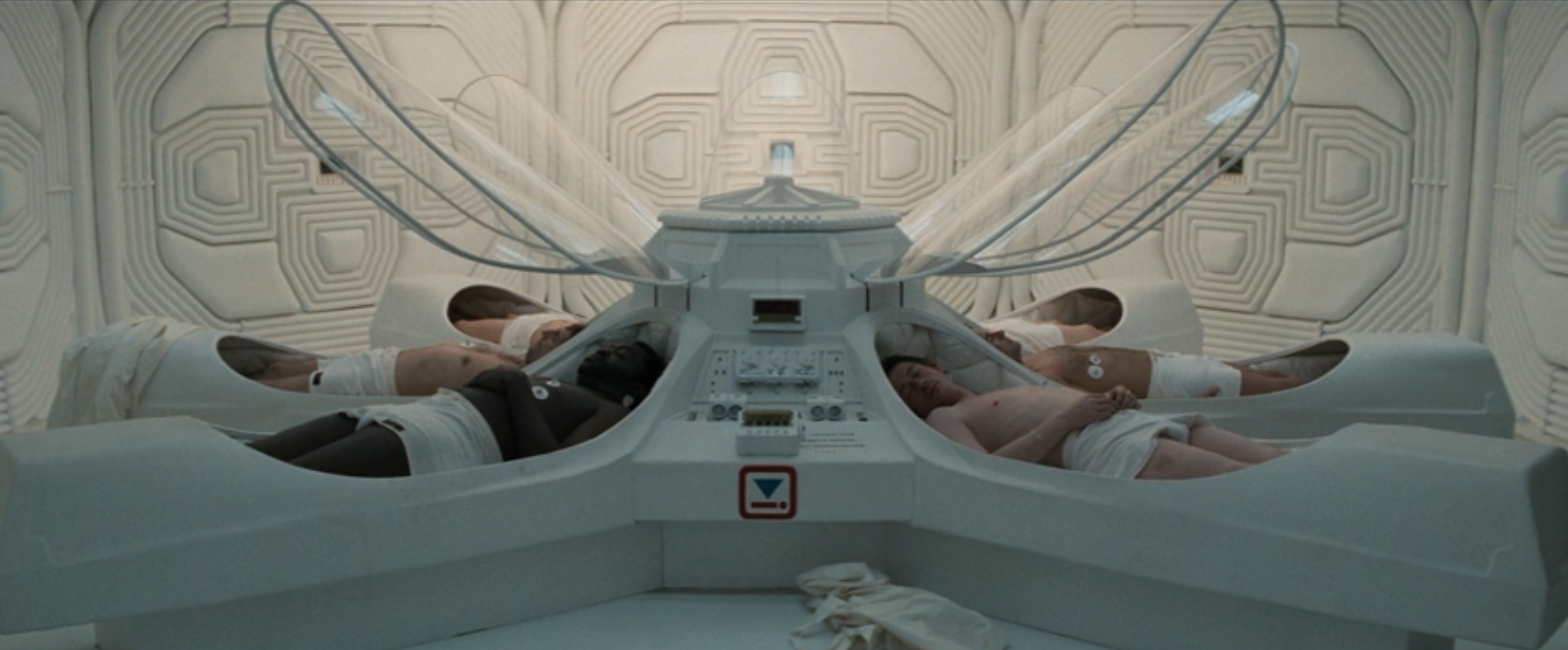

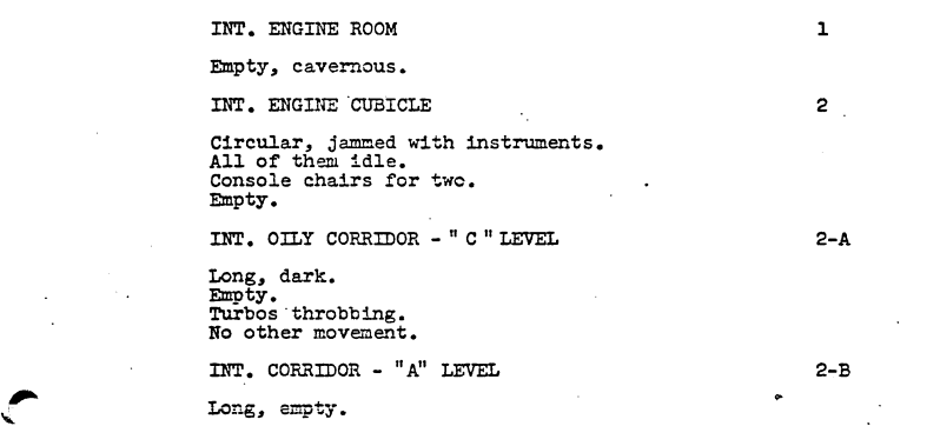

Inside, the ship is quiet and empty, its corridors lit but lifeless. The crew rests in cryotubes, dormant. The atmosphere is eerie, mechanical, detached – the ship sustains them, not the other way around.

The crew stirs groggy, arguing over pay and chain of command, revealing their working-class rhythms. We meet Dallas (Captain), Kane (Executive Officer), Ripley (Warrant Officer), Ash (Science Officer), Lambert (Navigator), Parker (Engineer), Brett (Engineering Technician), and Jones (Cat). I’ve always loved Jones; he humanizes the crew in this alien environment and makes me wonder what vermin might lurk in the ship’s dark corridors.

Their conversations are crude and casually familiar, perfectly illustrating them as overworked, blue-collar workers. Not pioneers or astronauts – more like truckers, right down to Brett’s gimme cap. I love how we’re thrown into it. The script is full of technical chatter, computing algorithms, piloting language – we feel lost, overwhelmed, like you’re thrown into a high pressure job on your first day.

A move that strict-structure purists might frown on – we’re not immediately sure who the protagonist is. Kane and Lambert dominate early scenes, throwing us in the deep end and creating a sense of unfamiliarity. The story lets us search for someone to follow, taking its time in settling on Ripley as our focal point.

INCITING INCIDENT

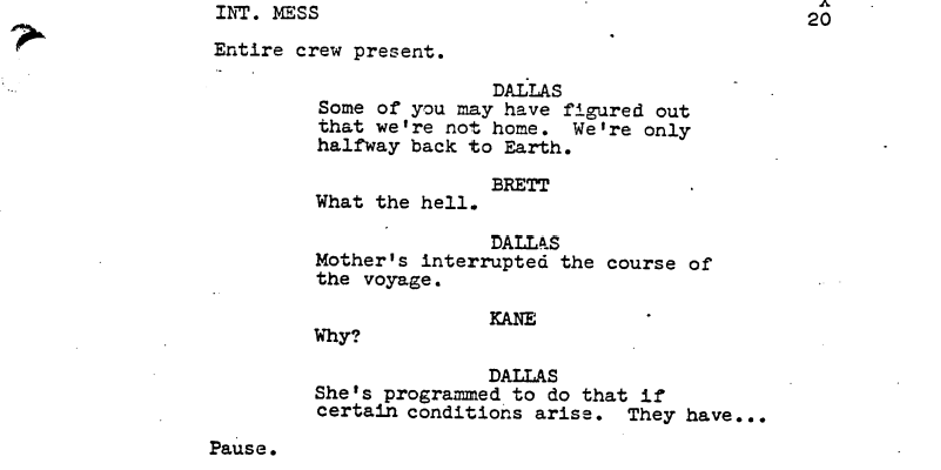

The plot kicks in immediately when the crew discovers that the ship’s system, ‘Mother,’ has rerouted them from their Odyssean journey home to respond to a distress signal on a nearby planetoid.

DEBATE

We dive straight into the debate phase, with tension simmering between officers and engineers asserting differing objectives. Kane asserts his rank to push the decision through.

The question of whether they should attend the distress call is quickly settled – but whether they can remains up in the air… as does the Nostromo itself. For ten pages, landing the smaller shuttle (the Narcissus) proves incredibly difficult, with storm-driven turbulence, rough terrain, and the constant threat of electrical fires. This isn’t the ‘use the Force’ Star Wars technique and it makes the difficult docking sequence in Interstellar look like parallel parking.

The resulting ship damage isn’t superficial, and Parker warns the crew they’re marooned for fifteen to twenty hours. They run diagnostics on the atmosphere and environment, estimating they’re about three kilometres from the distress signal.

BREAK INTO TWO

Kane volunteers to lead Dallas and Lambert out on the first expedition. Ripley stays behind – how unusual for our eventual protagonist to stand by while interplanetary exploration unfolds! Here, Ripley’s personality starts to emerge – a no-nonsense attitude toward select crewmates more eager for financial reward than goodwill.

FUN AND GAMES

Things take a strange turn when the crew discovers a derelict spacecraft – the source of the distress signal. It’s a disturbing sight which coincides with Ash losing contact with Dallas over long-distance comms.

The crew approaches the giant round vessel. Kane belays into the cavernous interior, venturing deep into uncharted territory. Back on the Nostromo, Ripley uses Mother to decode the transmission.

Ripley panics and proposes pursuit, fearing her colleagues are heading straight into the very danger they were warned about. Ash, however, refuses. It’s the first hint that Ash may have motives contrary to the crew – and the screenplay makes this much clearer than the film does.

Unlike the film, where all three explorers enter the ship and find the ‘jockey’ skeleton, the screenplay only sees Kane descend, radioing his colleagues from below. He enters the cargo hold and discovers leathery eggs within. Dallas warns him not to touch them, but the creature inside – the ‘Facehugger’ – pierces Kane’s helmet and latches onto his face.

When Kane stops responding, Dallas and Lambert winch him out of the ship and discover his ‘passenger’. Horrified, they rush him back to the Nostromo, where Ripley insists on a mandatory 24-hour quarantine – only for Ash to overrule her.

The crew monitors Kane, realizing the Facehugger is sustaining him. Attempts to remove it surgically draw acidic blood that eats through the metal floor. Ash spots a ‘stain’ in Kane’s lungs on the X-ray but dismisses the concern. Ripley quickly begins questioning the Science Officer’s disregard for quarantine protocol.

The Facehugger eventually detaches and dies, leaving Kane unconscious but seemingly unharmed. Ash insists they keep the specimen for research, with Dallas endorsing him – much to Ripley’s frustration. She voices her distrust of Ash, yet things appear stable: repairs near completion and Kane expected to recover. Everyone is eager to get home, so push their concerns aside.

Parker warns the repairs are temporary, so the Nostromo must be piloted carefully. After a tense takeoff, they reach orbit and celebrate with cold beers.

MIDPOINT

Kane wakes, seemingly fine besides residual aches and a ravenous hunger. The crew arranges a ‘last supper’ before ten months of cryosleep, bantering about what they’ll do with their shares. Then Kane’s newfound vigour suddenly gives way to despair.

The X-ray spot has gestated into a ‘Chestburster,’ which violently erupts and kills Kane. The crew watches in horror as the creature scurries away, turning their homeward journey into a nightmare hunt. Now the screenplay shifts fully into horror territory.

BAD TO WORSE

After sending Kane’s body into the cold crypt of space, the crew arm themselves and search the ship, a seemingly infinite task – you’ve seen the size of the Nostromo! Desperate to find the infant alien, they plan to trap it and eject it through the airlock. This scene also gives my favorite Ripley line: ‘I’m tired of talking.’ She’s ready to kick Xenomorph ass.

The crew splits into two teams, hunting the Chestburster in a deadly game of cat-and-mouse – highlighted when they mistake the cowering Jones for the alien. They assume the Facehugger is still small and weak, ripe for hunting, but in reality, they’ve become the prey. The Chestburster has grown to full size (the Xenomorph) at terrifying speed.

The crew reconvene sans Brett, determining the Alien has abducted him into the air shafts it’s using to navigate the Nostromo undetected. They’re hopelessly outmatched. Ash posits that most creatures fear fire, so Parker begins rigging flamethrowers.

Unlike the film, where Ripley volunteers to follow the Alien into the vents, no one steps forward in the screenplay. As captain, Dallas takes charge, with Parker and Lambert covering the maintenance-level exit, while Ripley and Ash handle the airlock.

Dallas enters the claustrophobic vents, trapping himself in with the Alien. The others monitor him using outdated, unreliable equipment, quickly receiving contradictory readings. Dallas tries to stay calm while Lambert panics – then abruptly goes silent.

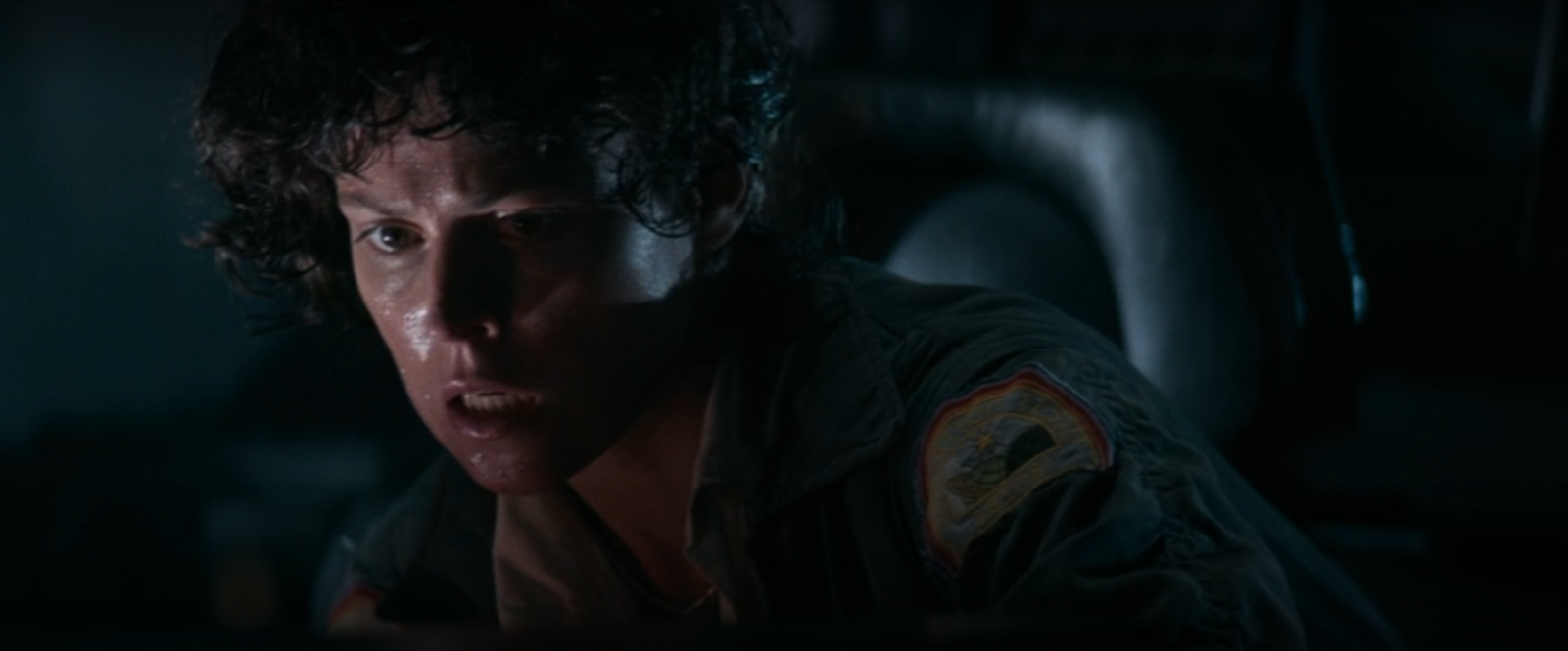

With their captain gone, the crew is shaken. Ripley, the pragmatist, steps into the leadership void, ignoring Lambert’s plan to abandon ship. Her suspicion grows as Ash (and Mother) fail to offer guidance.

BREAK INTO THREE

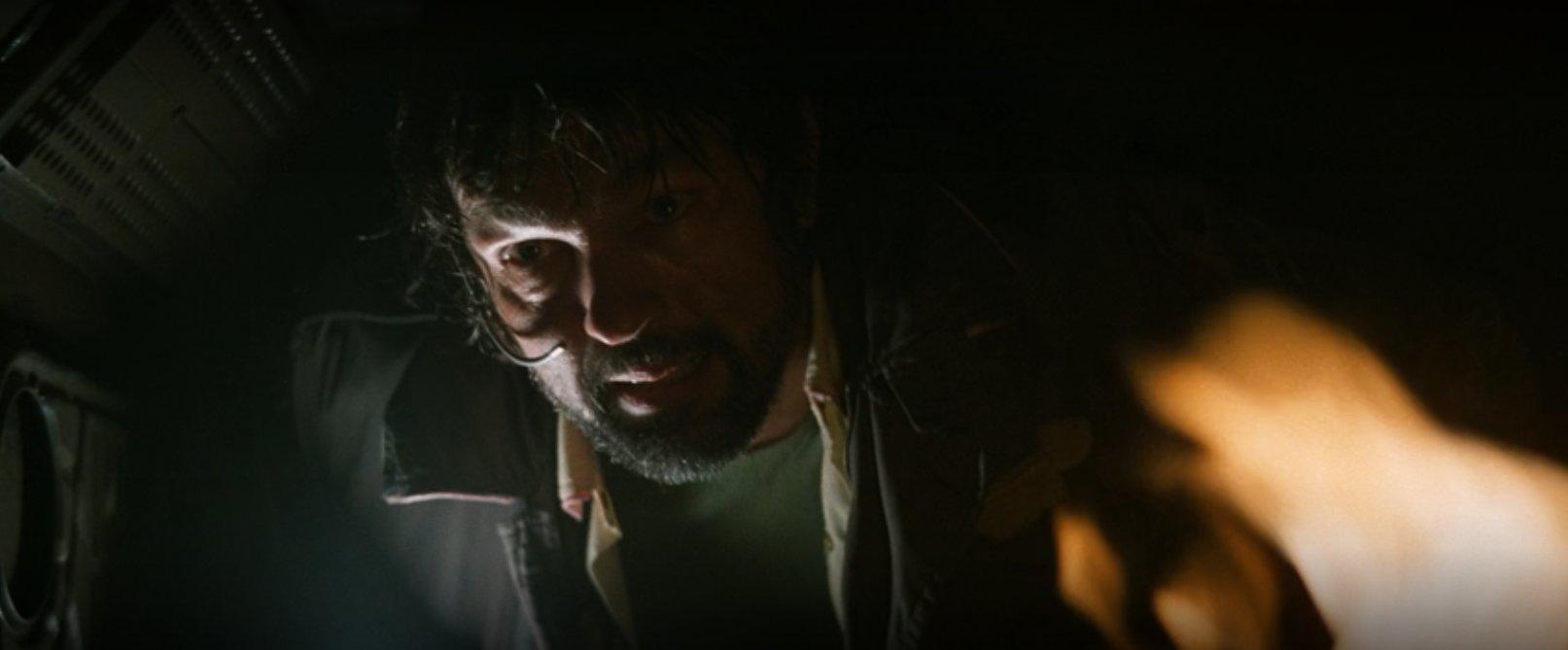

Parker and Ripley try to eject the Xenomorph through the airlock, but it fails, causing irreparable hull damage and loss of pressure – almost killing them both. Ripley now suspects Ash triggered the klaxon at the last second, sabotaging their survival efforts.

As we enter Act Three, the stakes escalate: the crew is being picked off one by one, and now there’s a traitor among them.

FINALE

Ripley uses her new seniority to consult Mother for guidance, discovering Special Order 937: the Company has instructed Ash to secure the organism, with the crew considered expendable.

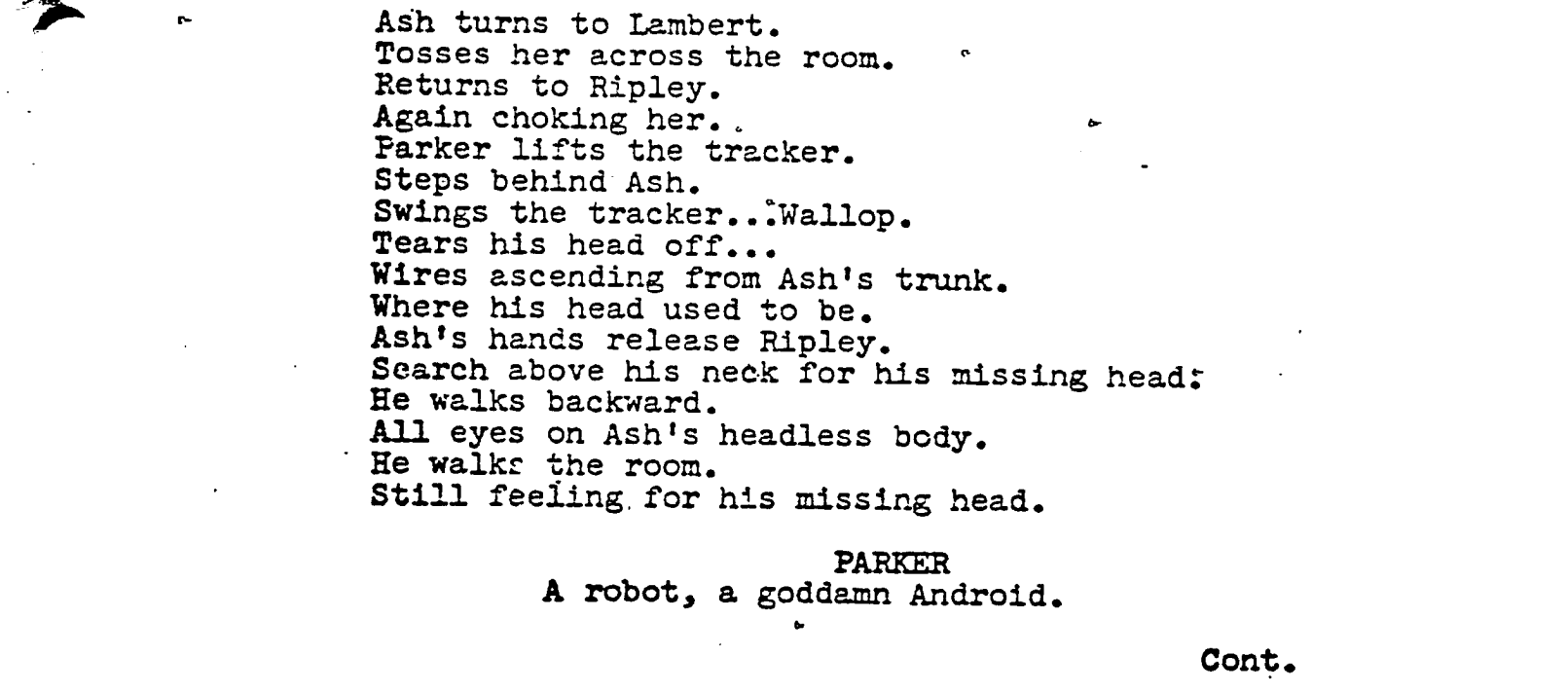

Chillingly, Ash appears behind Ripley. She flees the pod, fearing for her life, as he pursues her. Parker and Lambert intervene, decapitating him and revealing he’s been a Company-operated android all along.

In the script, the survivors reattach Ash’s head to interrogate him, so we miss the iconic detached-head exchange. Ripley deduces that the Company always intended the Nostromo to respond to the distress signal, and Ash was planted to make sure it happened.

The reanimated Ash confirms her theory, suggesting that the Alien is unkillable and even admiring it as ‘the perfect organism.’ His philosophy is inhuman, concerned with larger matters than ‘humanity’. Sick of his postulating, they pull the plug.

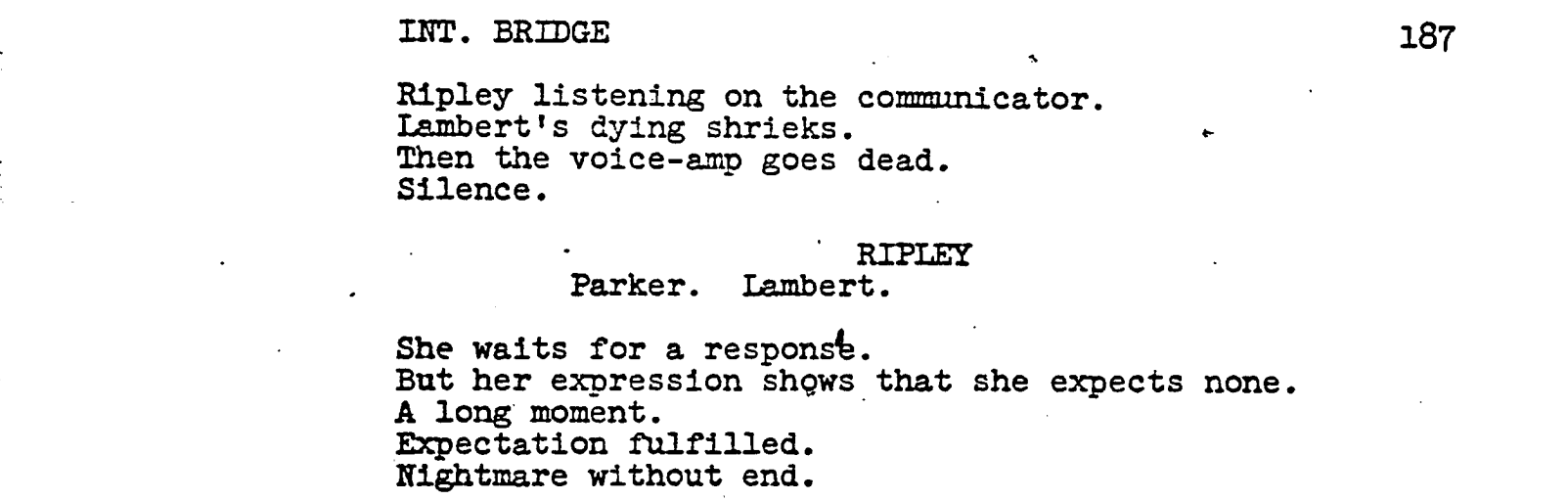

Ripley learns the remaining trio have under twelve hours of oxygen left. Lambert suggests using suicide pills meant to prevent a slow, agonizing death in space, but Ripley chooses a more altruistic path – planning to destroy the Nostromo to kill the Xenomorph and stop it from reaching Earth.

Armed with flamethrowers, they stock the Narcissus escape pod with coolant and supplies. While Ripley wrangles Jones the cat (a literal Save the Cat moment) Lambert and Parker are cornered and killed before escaping. Ripley arrives too late and finds their corpses.

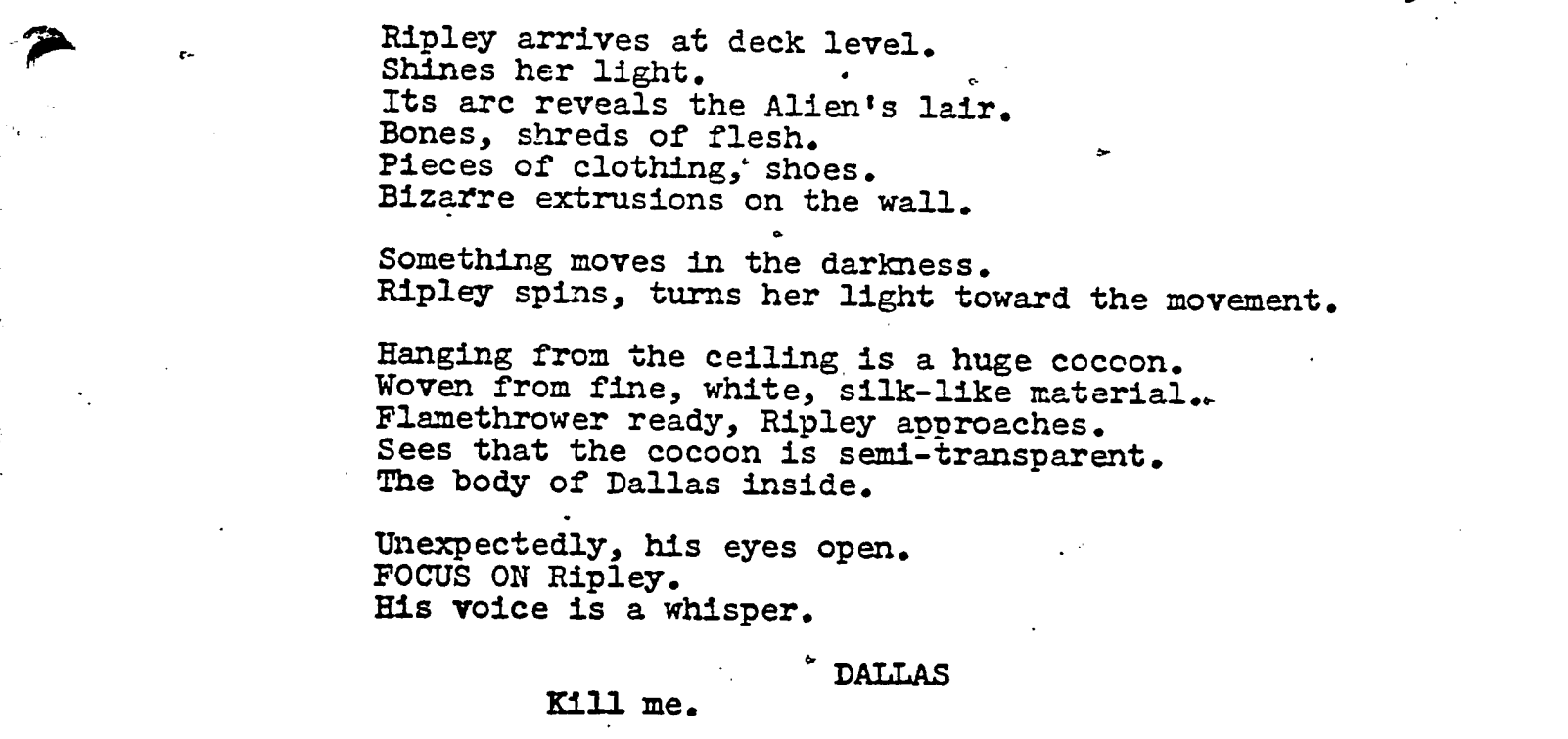

Now the sole survivor (barring Jones and the Alien) Ripley decisively activates the self-destruct. One of the script’s most striking scenes, cut from the theatrical release (the cocoon sequence later restored in the 2003 Alien: Director’s Cut), shows her stumbling upon the Alien’s lair, filled with grotesque organic pods housing the bodies of its victims.

Dallas begs for death, and Ripley obliges. I’ve always loved this scene – it opens a whole new layer of horror. The Xenomorph keeping Dallas alive raises questions, are there further steps in this twisted reproductive cycle? For Ripley, the situation is horrifying: she could leave him to die in the explosion but instead puts him out of his misery right away.

I’m glad the scene was cut, though, because it allows for the theatrical release’s ‘false ending,’ where the Xenomorph stows away on the Narcissus as Ripley prepares for cryosleep. While the long, tense finale with the destruct countdown and escape is powerful, this extra stinger takes the story even further – cementing the Alien as truly unkillable.

Panicked in the confined space, Ripley dons a pressure suit to flush the Alien out. She stabs it and opens the door to outer space, sending its acidic blood into the void. The Xenomorph follows and is incinerated by the jet’s exhaust.

Finally free Ripley retires, exhausted. Her and Jones are safe and alive.

CLOSING IMAGE

Signing off with a final message, Ripley returns to cryosleep, mirroring the film’s opening and framing the story like a waking nightmare. The silent stillness echoes the start, but where the Nostromo once bustled with life, the Narcissus is now utterly solitary.

CONCLUSION

Alien endures not just as a landmark in sci‑fi horror, but as a masterclass in screenwriting. Its tension is meticulously built, its characters are vividly realised, the antagonist is a near-Lovecraftian force of nature, and its narrative economy makes every scene heavy with purpose. From the claustrophobic dread of the Nostromo to the relentless, inescapable logic of the alien itself, the screenplay demonstrates how precision and passionate vision combine to create cinema that lingers.

I want to give a quick shout out to Walter Hill and David Giler, who, as mentioned, were left uncredited for this incredible work. They were reportedly deeply disappointed about this omission, though had no choice but to accept it. My understanding is that both had contributed substantially to earlier drafts of the script, especially in shaping the story’s structure, introducing the blue collar trucker atmosphere, and refining much of the dialogue. It must be painful to have been part of greatness and disheartening to be left out of its success – but screenwriting is a collaborative process and these things unfortunately happen.

The script is lifted by the incredible cast, the masterful design of H. R.Giger, the music, and Ridley Scott’s restrained directing. But like all great films, it starts with an ambitious idea – the type that transforms both how films are made and received. The version of Alien we were treated to is not the type of screenplay studios were ordering in the 70s, and if not for the unprecedented success of Star Wars two years prior (another spec!), this may never have seen the light of day. This proves the importance of writing the stories that are dear to you. Even if you can’t break through to studios, who knows when a surprise success will open doors for exactly the type of screenplay you’re already sitting on?

So before you prep your greasy typewriter to begin your next masterpiece, remember why Alien proves great writing is the impetus behind enduring masterpieces – and join us in celebrating the importance of the spec script in the Hollywood machine.

We award Alien a well-deserved 5/5.

Long live the spec!