Color, Time, and Voice: How Gerwig Reinvented Little Women

There have been many adaptations of Louisa May Alcott’s classic 1868 novel Little Women, but screenwriter and director Greta Gerwig took a big creative swing with her 2019 film. The original story follows a linear timeline, marking the passage from childhood to adulthood for the March sisters. Gerwig, however, decided to split the chronology, jumping back and forth from childhood to adulthood.

The result is a film that focused on the characters as adults rather than children, and in so doing, gave more insight to the women — perhaps most notably the character of Amy, played by Florence Pugh.

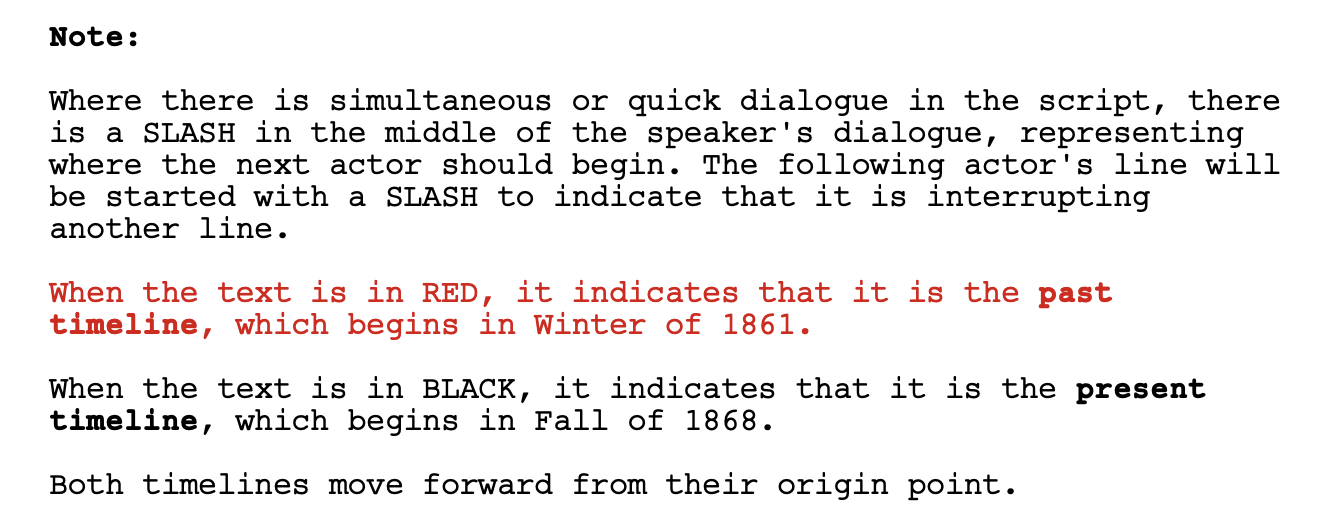

Structurally, in order to accomplish this, Gerwig made two rather notable screenwriting choices. First, she color coded the timelines, with red denoting events that took place in the past and black reserved for the present.

Second, she utilized a slash in the middle of speakers’ dialogues to represent where the next actor should begin simultaneous or quick dialogue.

These choices made for a confident script that paid off for Gerwig in folds.

OPENING IMAGE

From the very first line, Gerwig announces that Jo March is “our heroine” — and there is no other descriptor for her. Instead, Gerwig informs us of Jo’s nerves, her bravery, and what she is up against (a room — and a world — “full of men”).

Gerwig has a delicious mind and her screenplays brim with fun little moments. Consider the parenthetical on page two: “money over art” — she could have written something like: (decided) but instead she informed us not how Jo was behaving but what she was thinking.

There are more great little clues about Jo’s world that are given in quick succession, such as the editor informing her that female heroines must be married or dead by the end of a story. This was the world that our little women were growing up in.

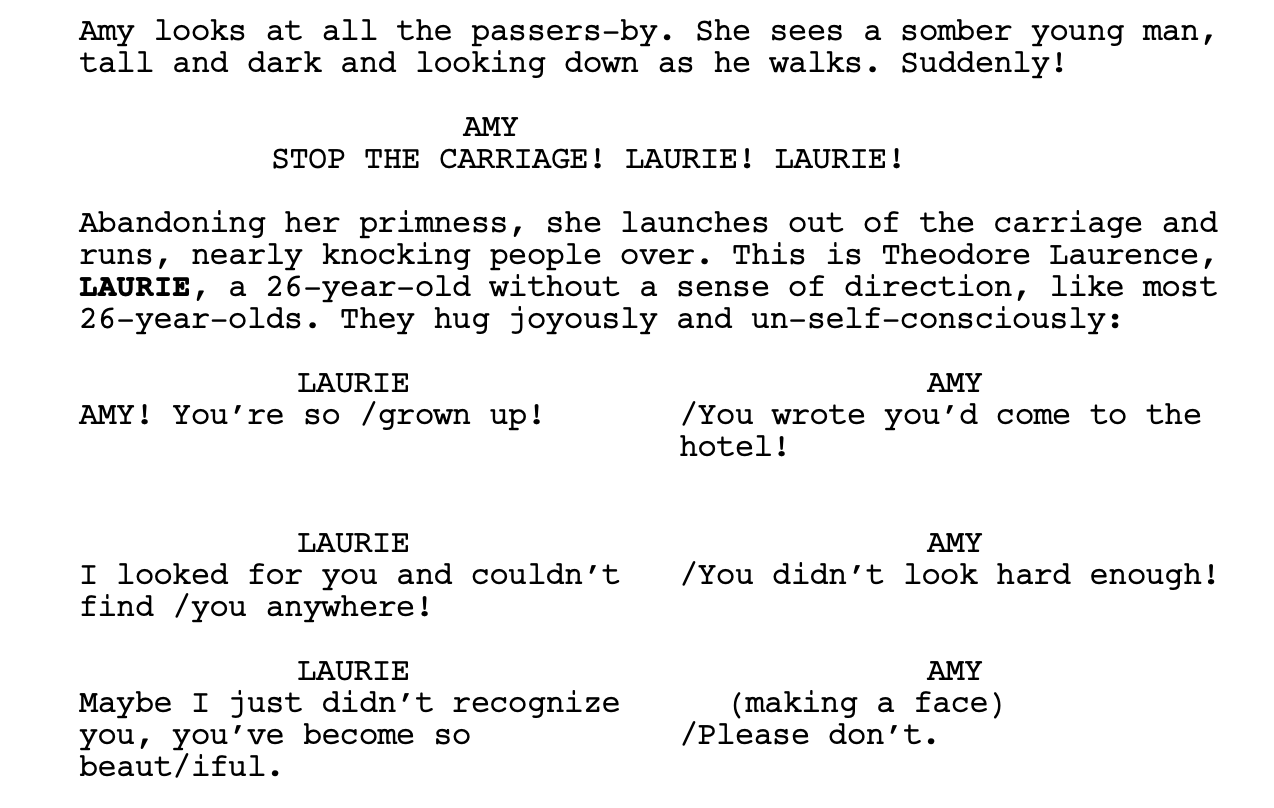

From Jo we move to Amy, who does get a descriptor (“an angelic 20-year-old with golden curls”). Amy’s life as an artist in Paris begins with very interesting subtlety that viewers of the film might miss.

Amy is the character who is served best by Gerwig’s time-jumping screenplay. In the original, Amy March, the youngest sister, is often an annoying foible for Jo — including (spoiler alert) when she marries Laurie, an act that always felt like a betrayal that came out of nowhere. But in this film, we first meet Amy as a grown woman with intelligence and ambition to match Jo’s. We also see Amy with Laurie before we ever see Jo with Laurie, an introduction to their relationship as adults and the mutual love that will grow between them.

Here, also, we see Gerwig’s use of the slash for her quick dialogue for the first time, a device often used in playwriting.

From Amy we move to Meg, modestly married with children. Then, it’s off to the past, notably, with only a fleeting introduction of Beth, alone at the piano in the empty rooms of her childhood home.

INCITING INCIDENT

And then, it’s off to the past, seven years before in 1861, where Jo and Meg ready themselves for a party. There, Jo meets Laurie, and the two bond over their lack of enthusiasm for such events. There are so many details about what is important to the girls as children. For Meg, this is a critical rite of passage — and one that her humble lifestyle simply doesn’t set her up for success in. Jo burns Megs hair. Jo burns the back of her own dress. Meg sprains her ankle dancing, to which Marmee observes “Oh Meg - You’ll kill yourself for fashion one of these days.”

Amy is disappointed to be left out. Beth watches it all, solemn and supportive.

So many little details are expertly woven in amidst the boisterous activity. Traditionally the inciting incident for Little Women is a gentle calling for the girls to strive for self-improvement and Gerwig’s adaptation is no different.

The girls’ wants and desires are still that of children — and while they won’t change much (Amy and Meg will still want refinement, Jo will pragmatically wish for funds without compromising her imagination, and Beth will harbor the wisdom that comes from a short life, which is that it is only our loved ones that truly matters), they will mature in their path toward womanhood.

It is Marmee’s love and guidance which first urges her girls toward generosity. On Christmas morning, she asks that they give up their already modest Christmas breakfast for a poor young mother and her five children who have nothing to eat.

Their clarion call is also in the wishes written to the family from their father, away at war: “A year seems a very long time to wait before I see them but remind them that while we wait we may all work, so that these hard days need not be wasted. I know they will be loving children to you, do their duty faithfully, fight their enemies bravely, and conquer themselves so beautifully that when I come back to them I may be fonder and prouder than ever of my little women.”

FUN AND GAMES

In the present — now 1869 — Jo tutors at a boarding house in New York where she continues to write and interact with a German professor, Friedrich. Abruptly, she leaves to return home.

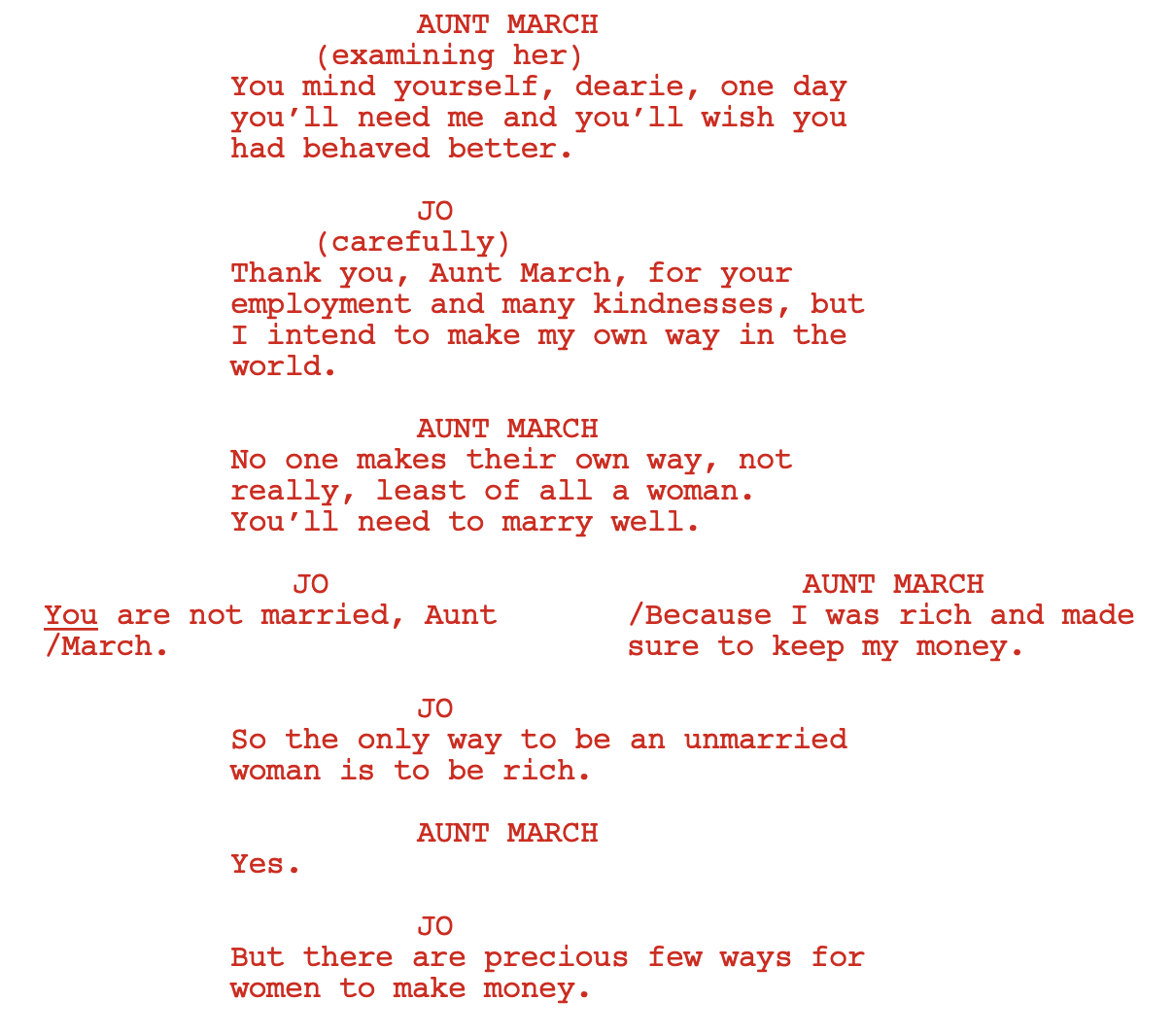

Back in the past, the holidays have come and gone and the girls return to school, responsibilities, and social structures of their peers. For Jo, that means reading to Aunt March.

Jo and Aunt March philosophize about what makes a life worth living — doing good or being comfortable — a choice that Marmee and Father March seem to have compromised on, which Aunt March looks disdainfully upon. They give up their comforts and what little money they have to help others and, in Aunt March’s opinion, that means they suffer. This is news to Jo.

Aunt March also teases a wonderful prospect: she intends to go to Europe one more time and she will need a companion, Jo.

Meanwhile at school, young Amy gets into trouble by being peer pressured (or rather, in Gerwig’s words, “seduced”) into drawing a very good and accurate caricature of their teacher, Mr. Davis, who whips her hand as corporal punishment.

She is invited home by Laurie, who sends for March aid. Meg and Jo appear and here Gerwig delightfully demonstrates the differences of the sisters…and the men who fall for them.

Jo is blunt, observant about Laurie’s wealth and library. Laurie indicates that while he may have material goods, he is lonely without the kind of family that Jo has. Meanwhile, Meg, attentive to Amy, entrances Laurie’s tutor Mr. Brooke. One bold drawing of a child has set life in motion.

A quick flash to the present, where Jo is arriving at home, much less lively than in the past. Even Laurie’s home is “dark, shutters closed.” The foreshadowing is clear, even to those who are unfamiliar with what befalls the March family.

But back in the past, the children bond with their neighbor Laurie, who fits right in with the March sisters. They are the family he has always pined for.

In the present, Jo arrives to Meg’s children, growing so fast, with Amy on a trip (“Amy has always had a talent for getting out of the hard parts of life,”) and Beth, very sick. Jo gives Marmee an envelope of cash for a doctor and announces that she will not return to New York, but will instead use her savings to take Beth to heal by the sea.

MIDPOINT

In the past, childhood rivalries heat up between Amy and Jo. Angry at being left out from going to the theater — and Jo’s impatient rebuttal of Amy’s feelings — lead Amy to burn Jo’s manuscript. Jo swears she will never forgive Amy, even when Marmee urges Jo not to “let the sun go down on [her] anger.” But Jo is resolute.

The next morning, Laurie takes Jo ice skating and Jo vindictively ignores Amy’s pleas to join. Amy follows anyway, crashing through the ice. Laurie and Jo just manage to save Amy from drowning, leaving Jo to grapple with guilt and self-reflection.

In many ways, Amy is a mirror for Jo. Their relationship will continue to be one of rivalry and competition, though at its heart they share not only creative similarities but a deep and loving bond. The truth is that Amy and Jo want similar things, but Amy learns how to behave in order to get what she wants. Unfortunately for their relationship later, when Amy and Jo want the same things, it is Amy who will get both and Jo will have to work on her own self-reflection about how she carries herself in her world.

BAD TO WORSE

In the past, Meg attends a debutantes ball, where Laurie is witness to how she changes herself to try to fit into the socialite world. “The young ladies walk down the stairs like fancy Easter Eggs, Meg the most beautiful of all. She’s a triumph…done up nearly beyond recognition. She’s powdered and corseted and drinking and flirting. In fact, she’s kind of great at it.”

But to Laurie, also in attendance, she is no longer herself, and he declares to her that he does not like the way she looks because he doesn’t like fuss and feathers.

In the present, Meg apologizes to her now husband, Mr. Brooke, for spending more than they could afford on silk for a dress. She confesses to him that she tries to be content but that it is hard and she is tired of being poor. Her honesty wounds him and she wishes she could take it back, but they both know it’s her truth. Meg has always loved wealth and refinement — but she made the same choice her parents made, to follow love. Her journey will be to accept that love and family and more important than wealth.

In Paris, Amy confesses her artistic frustrations to Laurie. “Talent isn’t genius, and no amount of energy can make it so. I want to be great, or nothing. I won’t be a common-place dauber, so I don’t intend to try anymore.” She informs him that she will just have to accept that it’s time for her to do what she was always meant to do: marry rich. He insists that it’s surprising coming from one of her mother’s girls.

ALL IS LOST

Here, Gerwig really shines with her choice to contrast the past with the present. She cuts from a time when the family went to the sea — Mr. Brooke and Meg flirt, Laurie is already in love with Jo, the children delight in the sea air. In the present, however, it is just Jo and Beth. “The beach is emptier, darker, colder — the beach of their adulthood, without the gloss of memory.”

Jo is at a dark place because things haven’t turned out the way she’d hoped. But Beth, who must know in her heart that her life will be short and reclusive, carries hope and wisdom like a flame.

In the past, Father is injured and Jo sells her hair to pay for Marmee to go attend to him. In Marmee’s absence, Beth cares for the poor Hummel family where she catches scarlet fever. As a child, she will recover, but as an adult, it will finally take her life.

In the past, Meg gets married and Jo learns that Aunt March has chosen to take Amy to Paris instead of Jo. Two of her sisters will be leaving Jo behind as their childhood comes to an end. When Laurie finally confesses his love for her, Jo panics and turns him down.

In the present, Jo wonders if she made a mistake turning him down. She realizes that if he asked her again to marry him, she would say yes. But that really isn’t the same thing as wanting to marry him. In one of Gerwig’s greatest scenes, Jo laments how conflicting it is to be a woman in a man’s world.

Unawares in Paris, Amy bets on her feelings for Laurie by turning down the proposal of Fred Vaughn — an ideal match. After Beth’s death, Laurie offers to bring her home to America and her family. Finally, adults who understand one another, “they embrace with both their joy and their grief. This is the way it was meant. It is done.”

He and Amy return home and Laurie breaks the news to Jo. “Jo, I want to say one thing, and then we’ll put it away forever. I have always loved you; but the love I feel for Amy is different — you were right — we would have killed each other. I think it was meant this way.”

FINALE

With Beth gone and her childhood best friend and potential sweetheart married to her now-grown little sister, Jo finally has a catalyst that drives her to write and submit to the Mr. Dashwood from the opening scene. Meanwhile, Aunt March passes away and leaves her grand home to Jo, in a surprise move. Jo decides to open a proper school where girls could learn just as well as boys.

Friedrich arrives at the March house, bringing with him some piano music — an echo of Beth — and new potential for Jo. He announces that he intends to go to California, with nothing to keep him in the east.

Meanwhile, Mr. Dashwood is stunned to discover that his family has read Jo’s manuscript about the lives of little women — and they are voracious for more. Perhaps there is merit in women’s voices afterall. But he wants Jo to marry off her main heroine anyway.

And here, Gerwig makes an interesting choice: the finale of her film, of Jo’s novel, and of this chapter in Jo’s life is left to interpretation: “The present is now the past. Or maybe fiction.”

Nonetheless, Jo publishes her book and opens her academy with Friedrich. Laurie and Amy are there with their child, and Meg and Mr. Brooke are there with their children. And they all seem to live happily ever after.