(More Than) 10 Screenplays that Break the Rules

Whether you're film school alumni, self-taught, or just getting into writing, you’re likely aware that screenwriting and rules go hand in hand. There’s a million rules and they’re constantly evolving. At some point you begin to ask yourself - why are these the rules and why should I follow them?

Let’s get one thing straight: a screenplay is a blueprint meant to communicate a story to the entire filmmaking team. If you’re writing something you’ll also direct and produce, then it’s yours - break the rules as you like. But if it’s a spec or someone else is directing, clarity matters. Following standard conventions helps ensure everyone’s on the same page - literally.

Knowing the rules and when to follow them is key, but so is knowing when to break them. The great 20th-century artists were classically trained before they bent the rules. Early Picasso and Dali looked nothing like their iconic styles! You need that strong foundation before you can defy it and truly express yourself. Subversion of expectation can be utilized with great effect, but only if you know what expectations you’re subverting.

Following the rules doesn’t guarantee success. I always stress this: if your story’s great, everything else is secondary. Just look at Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Pulp Fiction, or Lost in Translation - rule-breaking scripts that turned out brilliantly.

What’s standard today might feel outdated tomorrow, creativity is the mother of innovation. So today, let’s explore some standout scripts that break the rules - and are all the better for it.

THE SUBSTANCE - Check out our analysis here

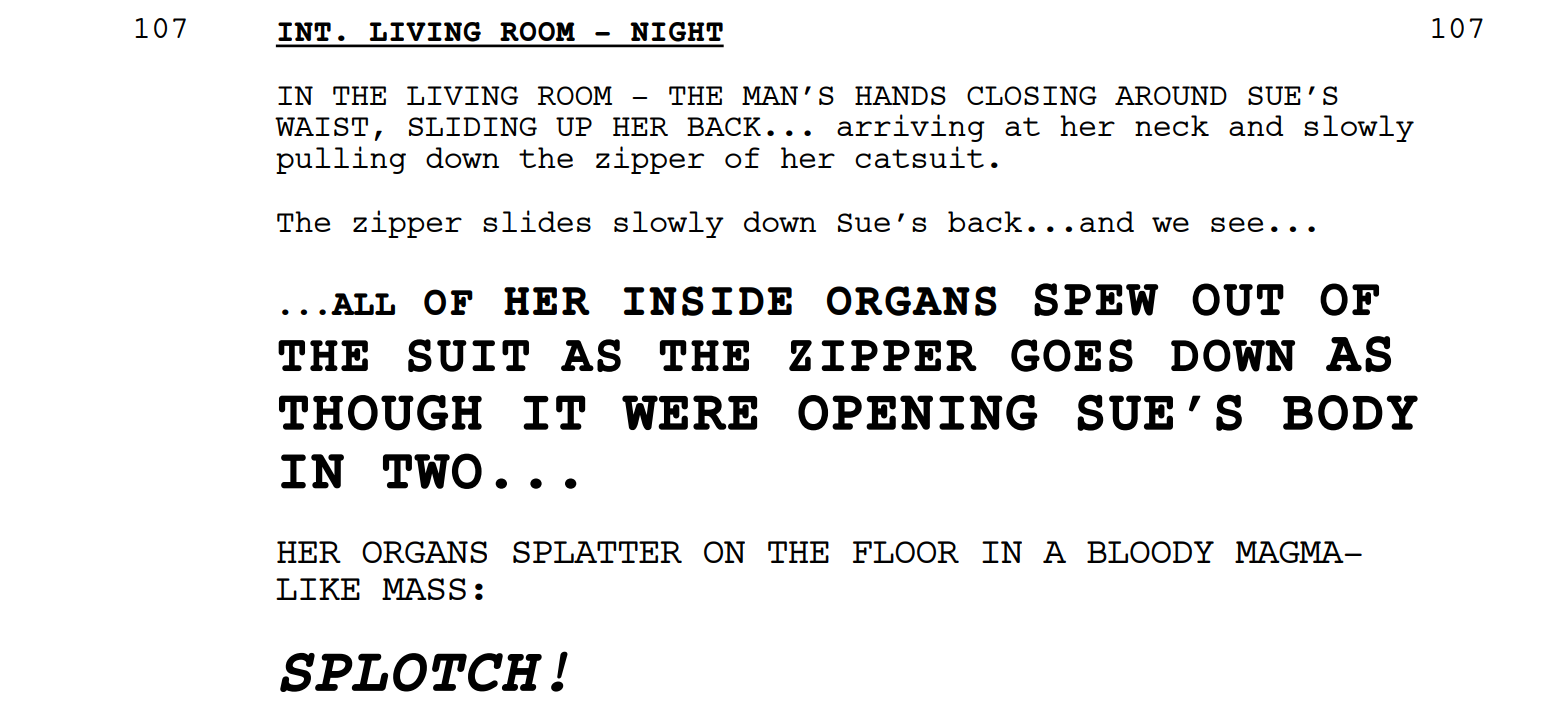

Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance, a Best Original Screenplay nominee, boldly breaks one of screenwriting’s most sacred rules: standard 12-point Courier formatting. Even if you know nothing else about scripts, you probably know they’re all supposed to look uniform.

Fargeat breaks from convention to grab the reader’s attention - especially during surreal or violent scenes - making you uneasy and signaling that you’ve entered a larger-than-life moment.

In Elisabeth’s call with her mysterious benefactor, the responses appear in action lines, not dialogue - preserving anonymity and creating a supernatural, almost internal voice, as if it’s coming from inside her head.

At times, the action lines slip into a stream-of-consciousness style, using Elisabeth’s thoughts as shorthand for actions or dialogue. Despite breaking plenty of rules, The Substance still earned wide acclaim and picked up accolades this recent award season.

Rules Broken: Formatting, fluid protagonist focus, rejects cause and effect plot.

THE TREE OF LIFE

Terrence Malick is a longtime Hollywood maverick - often said to start shooting without a screenplay to speak of, at the other extreme, to film so much he can cut the protagonist in editing as with The Thin Red Line. Let’s look at his seminal work, The Tree of Life, where he used a traditional screenplay but broke nearly every convention along the way.

Malick writes with childlike wonder, treating the screenplay like a living thing: a story told through the lens of a curious being who somehow knows this is a movie. It’s filled with introspection, Whitman-like poetry, and rhetorical questions - focused more on conveying awe than on visual or audio cues.

Relatively minor, but you might notice use of the phrase ‘We return.’ Using ‘we’ sparks endless debate in screenwriting circles - some hate it with a passion, others defend it to the death. Personally, I hate it because it was drilled into me by my first screenwriting mentor - but does it really harm the story? Not really. Some rules seem to be there for the hell of it and have no bearing on the quality of writing. Though this is the least of Malick’s ‘indiscretions’.

The screenplay meanders through time and space, skipping the linear three-act structure. It jumps back and forth, switches protagonists, lingers on prehistoric life crawling from the primordial soup for an uncomfortably long passage, and is filled with music cues and long voiceover passages. ‘Inconsistency is the rule,’ writes Malick in a screenplay largely about evolution. Given his distinguished career, this feels like a nod to how screenwriting itself has transitioned.

A traditionalist, Malick’s shooting script shows erased dialogue with handwritten replacements, revealing his preference for pen and paper over computers. Notice how action lines jump ahead in time and include what could be dialogue, but are written as action instead.

Because Malick shoots his own screenplays, he allows himself these lapses in convention. If I was reviewing this screenplay for someone trying to sell it on spec, I would have concerns, but because it’s in the hands of a master of the craft - it instead became perhaps my favorite film.

Rules Broken: Abstract act structure, prose, no clear protagonist arc, pacing, presentation.

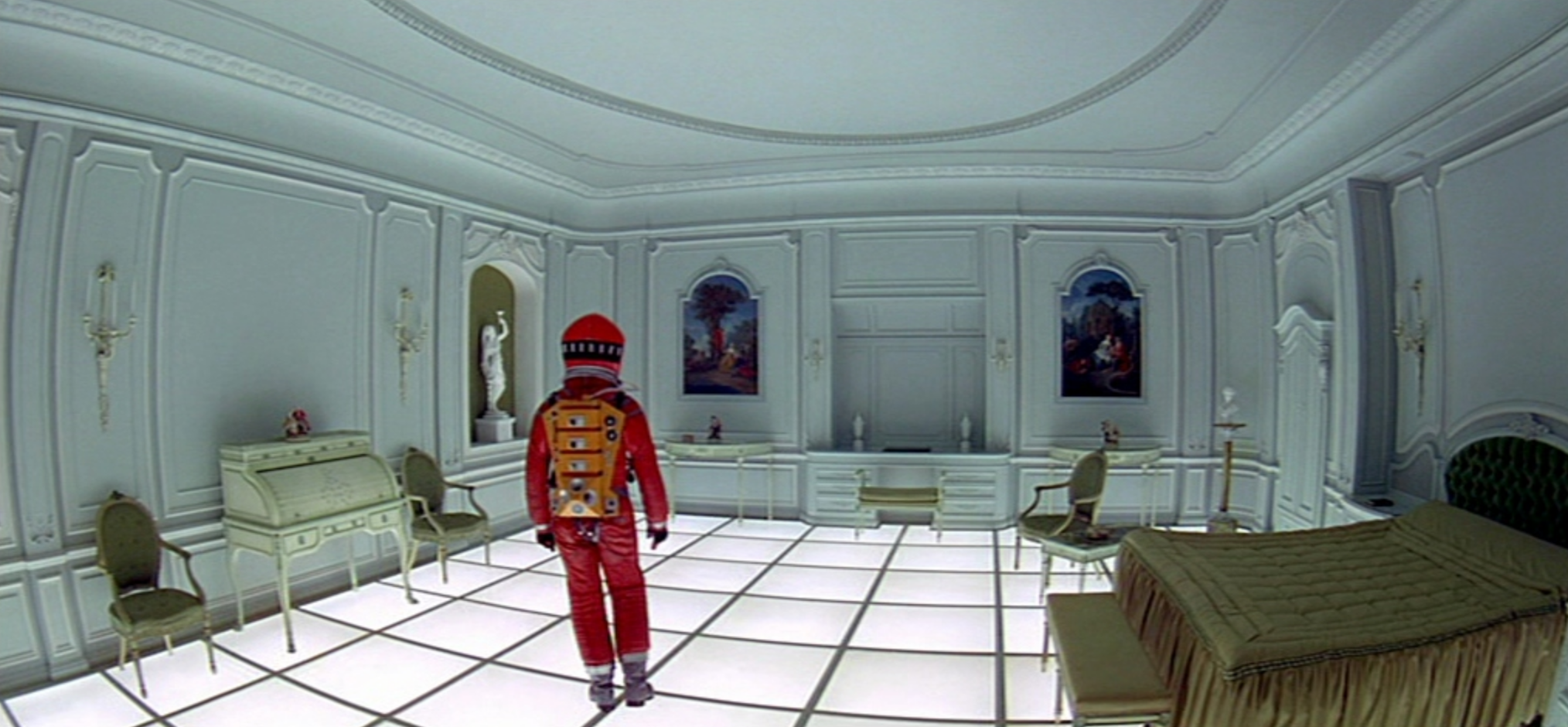

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY

Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clark’s sci-fi epic breaks just about every rule in the book with one hand, while creating new standards and commonalities with the other. Bizarrely, the two-and-a-half-hour film has a screenplay just 65 pages long. Some sections go many pages without dialogue, while some sections rely on nothing BUT dialogue. Prose-filled action lines guide Moonwatcher, an African ape from 3,000 years ago. Backstory is woven into action lines - not for the audience, but to give the monkey-suited actor context.

Perhaps the strangest rule break of them all, however, is how long it takes for a protagonist to be introduced. The screenplay waits until page 32 (the halfway mark!) to introduce Dave (Bowman), and it’s page 36 before we meet the iconic HAL 9000. That’s about 55 minutes, or 37% of the runtime! While the film set many standards, Hollywood never adopted such a late character reveal.

Early Hollywood screenplays were basically stage plays, but they evolved to handle sets, cameras, and large crews. While I don’t have stats handy, the ’50s and ’60s were probably the most unfocused era before conventions tightened up again. 2001 stands out as one of the most unusual (yet hugely successful) examples from that time.

Rules Broken: Heavy lifting from visual storytelling, short page count, lack of protagonist, prose, presentation, open-ended plot.

ADAPTATION

Charlie Kaufman’s Adaptation is one of the strangest screenplays I’ve ever read. It’s been 23 years since its release, and because it’s often hailed among the greats, we sometimes forget just how bizarre it really is.

Kaufman writes himself and a fictional twin (credited as co-writer) as main characters. The screenplay jumps through time and places, dipping into a screenplay adaptation by a man who rejects formula. Sounds confusing? It’s a miracle this film got made.

Additionally, for a screenplay about screenwriting, Adaptation makes sure you know it breaks the rules by drawing attention to their existence - sending Kaufman to a seminar on writing etiquette and underscoring the bizarre, archaic rules still parroted.

Rules Broken: Breaks the fourth wall, extensive voice over, eschews traditional plot arcs.

BONUS And if this isn’t weird enough for you, check out Being John Malkovich for more meta Spike Jonze / Charlie Kaufman craziness.

THE NEON DEMON

I want to discuss The Neon Demon, written by Nicolas Winding Refn, Mary Laws, and Polly Stenham - a screenplay that divides opinion. Not every rule break is a hit, as we see in this example. I love it because it eschews so many of the rules we come to expect. Audiences subconsciously sense familiar patterns, and sometimes note their absence.

Setup and payoff is one of the most basic storytelling rules - you see it in everything from epic novels to two-line jokes. When one’s missing, we take notice. When both are absent, we feel lost, uneasy, like we’re in a story that doesn’t add up. It creates a liminal space where reality and fantasy blur. And make no mistake - that’s totally intentional.

The script is minimal on dialogue but maximal on atmosphere, and the final film cuts even more lines from an already sparse script. When characters do speak, their lines are often clipped and cryptic, focusing more on intent and tone than plot or character. Below is an example - it’s hard to tell what anyone’s really saying in isolation.

The screenplay feels more like a descent into madness than a traditional three-act story, frustrating readers expecting clear arcs. This is highlighted by killing Jesse, the protagonist, with a full act left.

Screenwriters and readers often share similar backgrounds and education, so uncomfortable subject matter or presentation can often be dismissed as ‘incorrect.’ Refn, however, harnesses this discomfort, refusing to moralize expectations and constantly pushing boundaries.

Rules Broken: Ambiguous character motivations, subverts character empathy, lack of set up and payoff, visuals take precedent over story.

HELL OR HIGH WATER

One of my favorite examples is Taylor Sheridan’s Hell or High Water, which breaks the classic ‘less is more’ rule. As a writer often criticized for detailed prose or over-explaining visuals, I admire how he describes locations down to the temperature and faces down to the wrinkles. He doesn’t shirk away from being a visual storyteller.

Sheridan can’t help but lend his keen eye to his characters, so that the elaborately detailed appearances are highlighted and described to audiences, even when it’s irrelevant to plot or character growth.

Each description is full of details that don’t translate from page to screen, but Sheridan uses them to build atmosphere and crafts a unique experience.

At its core, this is a simple script in premise and execution - not a criticism, since doing basic well is tough, and Sheridan executes it with aplomb. But his prose and imagery lift it beyond a neo-western into something fresh and exciting, making it attractive to producers and cinephiles.

Rules Broken: No clear villains, subverts heist tropes, dialogue drives character instead of plot.

NIGHTCRAWLER

Dan Gilroy’s Nightcrawler feels breathless, partly because it ditches traditional sluglines. Instead of INT./EXT. and time of day, the script flows like a run-on sentence. Each camera cut becomes a subheading, guiding our focus and turning the script into a kind of storyboard.

Without periods or clean sentence breaks, the script reads like one long breath; pushing pace and momentum. Gilroy takes it further with ellipses, making it feel like we’re racing through, grabbing only fragments of info in a rush to the final page.

And then he does the complete opposite; suddenly, the rush halts for icy monologues made of short, clipped sentences. The emotion stays cold, but the pacing grinds to a stop.

The result is a gripping, one-of-a-kind ride - intense, immersive, and a masterclass in guiding the reader’s experience

Rules Broken: Slugline formatting, morally ambiguous protagonist, rejection of act structure.

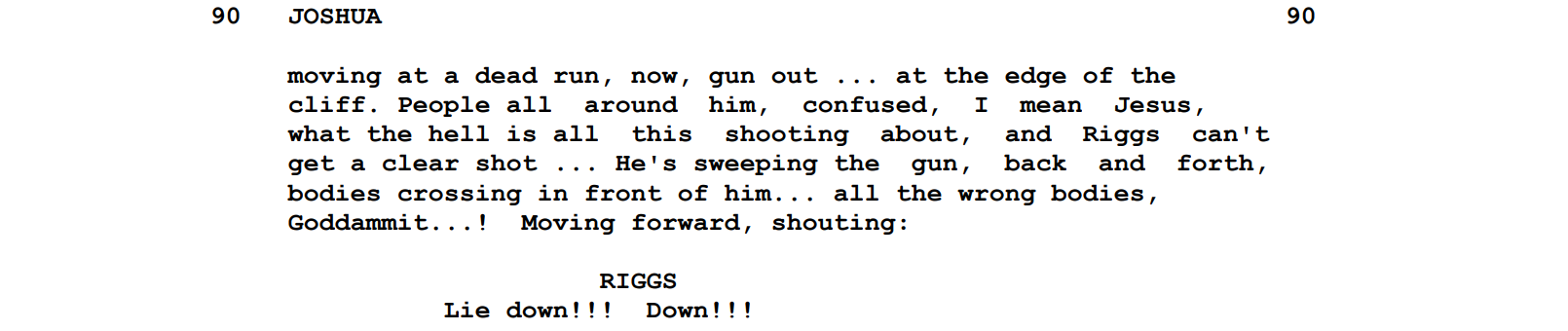

LETHAL WEAPON

If you know Shane Black’s work, you’re likely familiar with his offbeat script style - like in Lethal Weapon, where he breaks a cardinal rule by reminding readers they’re reading a screenplay. He even inserts personal commentary, turning himself into a kind of character. This is widely frowned upon as anything that disengages the reader from the story breaks immersion, but it absolutely fits in with Black’s idiosyncratic style.

Every character has personality, even random bystanders without a single line of dialogue are criticising the content of the scene and its content.

Rules Broken: meta commentary, screenwriter as a character, tone-breaking humor.

BONUS For more Shane Black self-referential nonsense, check out Kiss Kiss Bang Bang.

WEAPONS

Here’s a sneak peek - Weapons doesn’t hit theaters until August 2025, but after Barbarian shook up the horror world (and box office), Zach Cregger’s next film is already generating buzz.

From page one, we meet our narrator Maddie, who claims firsthand knowledge of the film’s events. This instantly gives the story a fable-like feel, reminiscent of a Shakespearean prologue. Additionally, the POV of a child lends an immature, misunderstanding lens to the story’s events. What would be horrific to an adult is mildly concerning to a child. This breaks several rules: we presume Maddie survives, undercutting suspense. It flies in the face of ‘show don’t tell’, a staple for any writer, with half a page of exposition over black. Her voiceover continues for five full pages before the story even starts.

What makes this even stranger is Maddie disappears after this - never heard from again - just like the children of this story. She’s just an anonymous narrator. I always advise writers to give their voiceovers clear motivation: who they’re addressing, their intent, whether they’re reliable or otherwise. These shape how narration is crafted. Cregger, however, skips this important step.

The story starts unusually late. We skip the typical setup: no time spent getting to know the children or Justine as a caring teacher. By the time things begin, the inciting incident has already passed, throwing us into the deep end. This trades emotional connection for a gripping, immediate hook.

I usually tell new writers to skip music cues in screenplays. If the scene only works with the song, it’s not a strong scene. Music rights are expensive, hard to clear, and can complicate the edit. That said, if you’ve made a hit like Barbarian and you're directing it, you can do pretty much whatever you want.

The screenplay jumps between POVs - starting with a teacher, then a grieving parent, a cop, a homeless man. It stays cohesive, but unfolds in a more episodic, fragmented way. This makes it difficult to fully connect with characters because we know our time with them is fleeting.

And lastly, the screenplay keeps the villain hidden until the final third, without much foreshadowing or misdirection at play beforehand. Confusingly, their objective and the scope of their scheme isn’t explained, meaning the plot feels like it revolves around a random act rather than part of a motivated plan.

Rules Broken: Music cues, shifting protagonist, classic narration, absent villain motivations.

CAPTAIN AMERICA: THE FIRST AVENGER

Now hold on - I hear you ready to complain: superhero movies suck, you want to talk about real cinema. But I include this to show that even big-budget blockbusters don’t follow every rule

In The First Avenger, we invert the usual ‘refusal of the call.’ In most every hero’s journey, there’s a point where the hero says ‘no, what you’re tasking me with is too big for me to handle.’ Once you’re aware of this, you’ll find it present in almost every story - whether it abides by the formula of the Hero’s Journey or not.

Conversely, during this debate phase, Steve Rogers is eager to answer the call - he wants to serve his country - but no one will let him, while others are chosen around him. It works beautifully: we share his frustration, admire his persistence, and it bonds us to him for half a dozen films to follow.

Rules Broken: discards hero’s journey, incapable protagonist.

BONUS For further example on ‘accepting the call’ (or fighting Nazis, which seems to be a recurring theme) look at Raiders of the Lost Ark.There isn’t a moment where Professor Indiana Jones says ‘I can’t go stop those guys right now, I have homework to correct.’ As soon as the offer is on the table - the inciting incident - he’s gone.

Conclusion

Honorable mentions that you can check out for more information on atypical screenwriting practices: Mulholland Drive, Past Lives, The Big Lebowski. These are some cult favorites with their own rule breaking techniques, which we dive into in more detail.

If there’s one takeaway from all this, it’s that screenwriting rules aren’t sacred. They’re just patterns - evolving norms shaped by what’s worked before, not what has to happen next. Every great screenplay doesn’t just follow rules - it bends them, twists them, or tosses them out entirely to make something fresh. Think about it: each of the scripts we’ve looked at rewrote the rulebook in its own way, minor or major as it may be.

The truth is, there’s no one-size-fits-all formula. What matters isn’t whether you hit every beat of the Hero’s Journey, write sluglines perfectly, or avoid narration - because a screenwriting guru told you to. What matters is how clearly and powerfully you communicate the heart of your story. That’s it. If you can pull that off - whether through voiceover, fragmented structure, or lyrical prose - then you’re doing it right.

So by all means, learn the rules. But don’t be afraid to break them. Sometimes, breaking the rules is exactly how you get noticed.