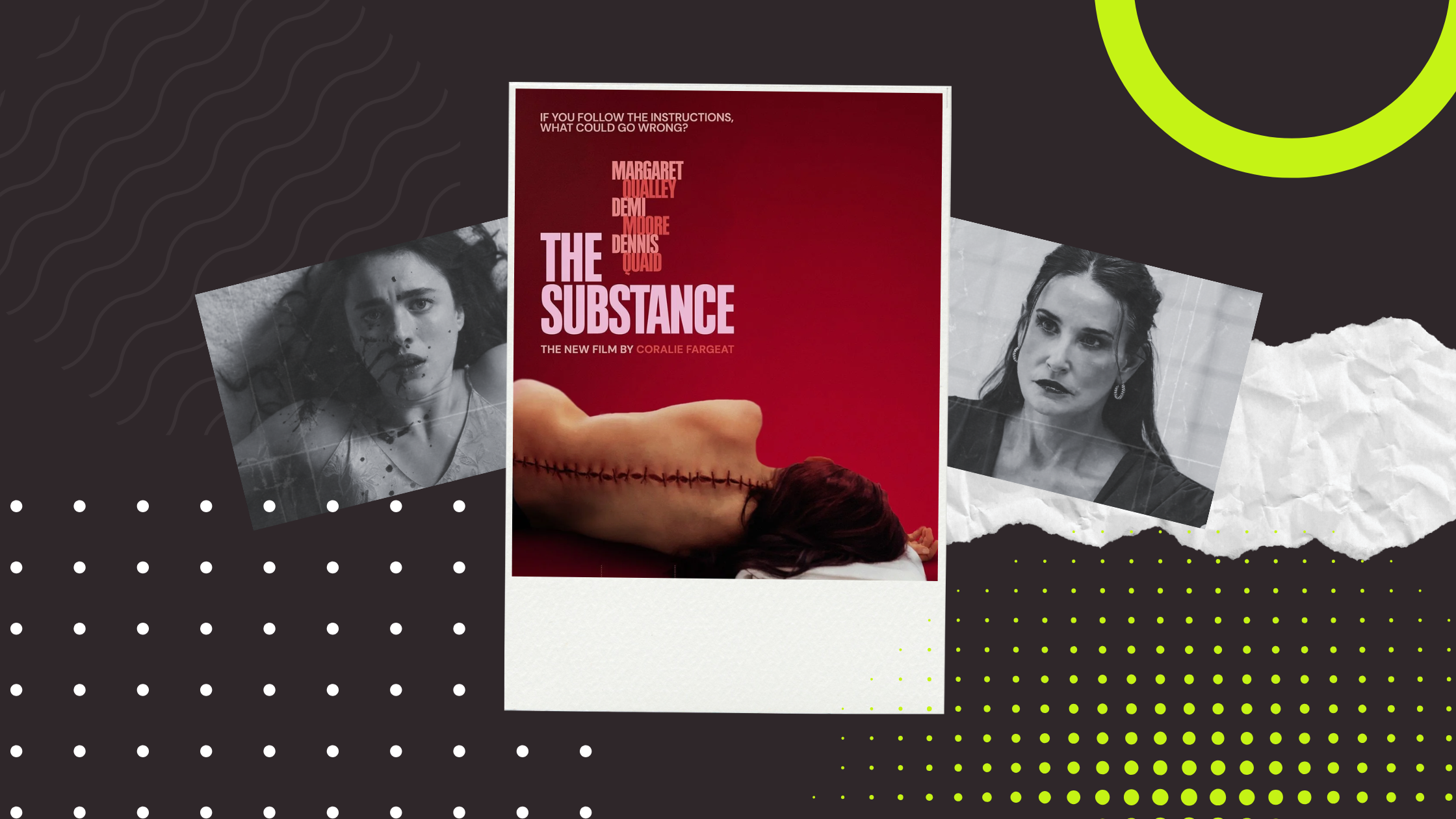

Style Over Substance? How Coralie Fargeat Achieves Both.

Screenwriter / Director Coralie Fargeat is back after the success of 2017’s Revenge, but surely her sophomore film won’t be quite as bloody… right? Wrong. The Substance is already proving a runaway cult hit both in theaters and on streaming. The satirical Cronenbergian body horror isn’t only capturing the interest of cinemagoers, but critics too, bagging Best Screenplay at the Cannes Film Festival. In its slow rollout (discounting streaming deals), the film has already turned a profit against its $14.5 million budget, and with releases yet to come in many markets - including Fargeat’s native France - those numbers are only climbing.

Let's dive into Fargeat’s 2020 screenplay, dissect and discuss it, and examine what was left on the cutting room floor for the 2024 theatrical release.

Opening Image

The stage is set with two opening images that establish the elevated reality of the screenplay. First, we see the yolk of a raw egg injected with ‘The Substance.’ The yolk duplicates through a process of mitosis - only this time, it comes out rounder, shinier, and flawless in every way. Next, Elisabeth Sparkle’s star is added to the Hollywood Walk of Fame. At first, there's a flurry of excitement, but as the decades pass, it becomes neglected. It weathers under the sun, cracks with age, and gets trampled by indifferent passersby.

Immediately, we establish the device of the screenplay, the titular Substance, and an accessible, condensed social commentary on how the sparkle of celebrity wears off with age. This also serves as a bookmark image which can be mirrored by the closing image. But more on that later.

Set Up

Elisabeth Sparkle is a fading star in an ambiguous Hollywood era. Once an Oscar-winning actress, she's now a middle-aged Jane Fonda type, hosting a weekly at-home workout show in bright lycra. Used to being adored by the public, she feels age creeping up on her, heralding the end of her career. We meet her on her 50th birthday.

Those fears come to life when network director Harvey (no prizes for guessing who he’s parodying) and manager Craig (who doesn’t make it to the final cut) drop her. In an instant, the attention she’s always thrived on is pulled out from under her. She feels discarded.

Fargeat brings the world to life with larger-than-life characters while tapping into very real insecurities and industry practices. Elisabeth is instantly relatable and easy to root for as a sympathetic character. Even though she’s somewhat passive in this part of the story, the exaggerated caricatures of the people around her make them detestable in comparison.

Inciting Incident

After a car accident inadvertently caused by her intense emotional state, Elisabeth catches the eye of an unnamed nurse who identifies her as a ‘suitable candidate’ for THE SUBSTANCE—an opportunity to transform into a ‘younger, more beautiful, more perfect’ version of herself.

This is a classic inciting incident or catalyst moment - an accident shakes Elisabeth from her stasis, puts her in the line of vision of new parties and generates new narrative possibilities.

The Debate

Despite her rock-bottom self confidence and rising despair, Elisabeth initially refuses this ‘call to adventure’, following a typical hero’s journey arc. This moment of resistance is important; it lets her - and the audience - pause and wonder what she might be missing. As in real life, the fear of missing out is a powerful motivator. Just like in real life, the fear of missing out becomes a powerful pull. After a period of wallowing, feeling like the world is moving on without her, she concludes that embracing this opportunity is the only way to keep up.

She calls the Supplier and gives her details. The moment she makes this choice - before she even receives THE SUBSTANCE - she already feels a lift in her spirits. She nurses her hangover, shrugs off an advertisement to replace newly vacated job, and picks up the kit that promises to change her life. By taking this step, she regains a sense of control, and it validates her newfound optimism.

If you’ve only seen the film, this last part might not match up with what you remember. It’s one of several tweaks made between the screenplay and the final cut—more on that in the section “CHANGES FROM SCREENPLAY TO SCREEN.” Either way, this decision signals a turning point, marking a new wave of proactivity for Elisabeth after a stretch of self-doubt and uncertainty.

Break into Two

By taking THE SUBSTANCE, Elisabeth violently ‘births’ a young version of herself, an entirely separate entity who will become known as Sue. As the mysterious Supplier explained, Elisabeth can spend seven days as Sue, but must then revert to being Elisabeth for the following seven days, requiring daily ‘stabilization’ through a spinal fluid injection. Elisabeth is warned that she must make this swap every seven days without fail; any deviation from this crucial cycle will lead to serious consequences.

As we enter Act Two, the stage is set: our protagonist is now fractured into two distinct individuals, the younger of whom allows the elder to begin regaining some of the attention she craves. The bloody and horrific nature of this human mitosis foreshadows the dark events that lie ahead. Beyond the psychological and biological terror, this transformation serves as a sharp satire, underscoring the vices of the relentless quest for eternal youth and adoration.

Fun and Games

‘Sue’ bleeds from her nose before extracting Stabilizer from Elisabeth, allowing her to find equilibrium. Fresh, flexible, and irresistibly seductive, she embraces her newfound youth, flirting her way through studio security. She quickly secures a role hosting an at-home workout show - ‘Pump It Up’ - back at Harvey’s network. When asked for a name, she lands on ‘Sue’, a cover which differentiates her from Elisabeth, but proves a fork in the road.

Effortlessly finding herself as Harvey’s new star girl, Sue has achieved what Elisabeth failed at, giving them sharply juxtaposing trajectories and establishing a relationship primed for jealousy.

Sue builds a secret hidden room within the dead space of her apartment walls (illustrating a surprising aptitude for construction) in which she can store Elisabeth and the medical supplies required for the swap. She concludes her seven days as Sue, rehearsing choreography for her new show, then completes the procedure and awakes as Elisabeth once again.

Elisabeth realizes how quickly she’s been eclipsed by Sue, struggling to feel like both aspects of herself as truly ‘her.’ Despite this envy, her week in charge drags on, almost as if she’s living vicariously through Sue’s vibrant life. She spends her seven days aimlessly rotting in front of infomercials on TV, feeling increasingly disconnected from her own reality. She is already forgotten by Harvey and the network, as Pump It Up is proving a major success. Sue has replaced her entirely.

Ex-manager Craig Silver approaches Sue, eager to represent her despite his past excuses of downsizing when firing Elisabeth, but she dismisses him in favor of another manager. On the seventh day as Sue, she goes out to celebrate with friends and colleagues. She brings home a hook-up, coinciding with when she’s supposed to swap back to Elisabeth. She overstays her welcome as Sue, breaking the balance. As he undoes Sue’s catsuit, she falls apart, covering him with blood and guts.

Midpoint

Elisabeth wakes up to find that the previous experience was just a dream, but she’s shocked to see that her hand has aged and withered due to Sue’s delayed body switch. This deepens her resentment toward Sue - she’s envious of her youth and vitality, but she also realizes just how much she relies on her.

This moment serves as a powerful midpoint, physically illustrating the animosity and ‘borrowing’ happening between the two women. What one does has a direct impact on the other, highlighting how their ambitions are diverging rather than coming together.

Bad to Worse

When Elisabeth calls the Supplier to voice her frustrations about Sue’s actions, she is swiftly reminded that she and Sue are one and the same - a message that they have attempted to drill into her from the beginning. She is reminded to respect the seven day balance. This recontextualizes what ‘balance’ truly means for Elisabeth. It cleverly flips the solitary rule associated with this seemingly free and highly advantageous process on its head, revealing the complexities of their intertwined existence.

Further disgusted by her own aging body, Elisabeth languishes, attempting to rejuvenate her age-spotted finger with regenerative anti-aging cream, which unsurprisingly fails. She becomes increasingly irritated by noises around her, and the repetitive nature of Sue’s show on TV becomes a trigger. Any attention she receives as Sue, she feels unworthy of as Elisabeth, hiding from neighbors and covering herself with gloves and sunglasses in public.

Elisabeth encounters another subject of THE SUBSTANCE, identifying him as the older version of the nurse who shortlisted her. He shares her frustration about the tedious ‘off weeks’ where they’re relegated to their old bodies. Even though they’re in the same situation, Elisabeth feels ashamed by her own actions and denies any knowledge of the process.

Desperate to feel beautiful in her own skin, she reconnects with Fred, an old acquaintance from school who still shows a slightly creepy interest in her. They set up a date, but no matter how hard she tries to dress up and perfect her makeup, she cannot help but compare herself to Sue. In a prolonged, heartbreaking sequence, she lets the clock run later and later in search of perfection. Overwhelmed, she ends up ghosting Fred.

While Act 2A primarily centers on Sue’s progress, Act 2B shifts its focus to Elisabeth’s regression. We witness Sue beginning to resent Elisabeth in 2A, and in contrast, Elisabeth starts to learn to hate Sue in 2B. Their journeys function as mirrors of one another, structurally as well as in terms of character development.

While taping an episode, Sue suddenly feels an unsettling bulge beneath her skin. Self-conscious about it possibly showing up on camera, she takes a break to inspect her ‘perfect ass’ (for anyone curious, ‘ass’ is referred to 27 times in the screenplay, along with 17 mentions of ‘butt’ or ‘buttocks’ and 3 instances of ‘rump’). She manages to navigate the mass to her belly, then extracts it through her navel - revealing it’s a greasy chicken drumstick.

Sue awakes in a cold sweat, discovering this was (yet another) fake out dream, triggered by Elisabeth’s heavy comfort eating. Repulsed by her older self, Sue’s disgust deepens the growing rift between them—they're no longer the same person as they evolve in such opposing directions. Frustrated, Sue calls the Supplier to complain about Elisabeth, but they reiterate the same point: they are one and the same.

Harvey summons Sue, igniting fears that her secret might have somehow been uncovered. However, he brings good news: she’s been booked for the New Year’s Show - a live event that comes with significant responsibility. While she’s thrilled to have been chosen, this creates a dilemma for Sue. With all the rehearsals and obligations piling up, she justifies ignoring the prescribed balance, leaving Elisabeth ‘uninhabited’ for months at a time.

Break into Three

In a rare return to consciousness, Elisabeth realizes she has grown old and arthritic because Sue has been ‘borrowing’ her time. The effects that once showed on her hand have now spread across her entire body. Frustrated, she reaches out to the Supplier again, who reminds her that she can end the process if she wants to. As she contemplates this choice, she learns that Sue is thriving—landing the cover of Vogue and securing a role in an exciting film opportunity.

We’re poised nicely going into the finale; It hits Elisabeth hard: Sue is accomplishing the life Elisabeth hoped for by taking THE SUBSTANCE, but she is witnessing it from the sidelines. The thought of terminating Sue looms over her, yet that decision would leave Elisabeth not only prematurely geriatric but also without any chance of ongoing success.

Climax

Sue has a boyfriend at the apartment the night before the New Years Show. She panics when she discovers that she has run out of Stabilizer, and Elisabeth’s aging body has no more spinal fluid to extract. She complains to the Supplier, who informs her that she must live a week as Elisabeth for the fluid to regenerate. This is highly inconvenient timing for Sue on the eve of her crowning success, forcing her to return to Elisabeth’s body in a hurry, fearing deterioration.

When her boyfriend risks discovering that Sue has transformed into an old crone - well beyond the bounds of realistic human aging - they both freak out. In the chaos, Elisabeth kicks him out of the apartment. In a moment of clarity, she vows never to return to Sue, terrified of losing control forever. She tells Craig Silver that Sue is not coming back.

Elisabeth receives a termination liquid from the supplier and uses it to kill Sue’s body. Almost immediately, she realizes the magnitude of what she’s sacrificed and regrets her decision. She tries to resuscitate Sue - and to her surprise, she succeeds. Both bodies now share consciousness simultaneously. Feeling betrayed by Elisabeth’s attempt on her life, Sue fights back and ultimately kills her originator, sealing their fates in a brutal, violent whirlwind of survival and desperation.

As well as the New Years Show serving as a ticking clock - with less than 24 hours to go - we now understand that Sue’s body is doomed. Without the daily Stabilizer, will she make it to fulfill her responsibility?

Without the means to maintain her youthful form, Sue starts to fall apart backstage in the chaotic lead-up to the New Year’s Show. Desperate to keep it together and succeed, she rushes home and discovers a small vial of activator fluid from her original metamorphosis still remains. In a moment of frantic determination, she injects it, leading to a shocking transformation. Instead of preserving her original self, the fluid births a monstrous, mutated third persona known as Monstroelisasue.

The mutant amalgamation returns to the set, wearing a cut-out photo of Elisabeth’s face in a desperate attempt to mask her own grotesque appearance. As the creature steps onto the stage, it incites mass panic among the audience, including Harvey and his shareholders. In front of millions, including a live crowd, she continues to mutate, spurting blood all over the studio and turning what was meant to be a celebration into a scene of chaos and horror.

Final Image

The deteriorating mush escapes the riotous scenes, crawling away from the studio. In a haunting echo of the film's cold open, Monstroelisasue makes her way to her weathered star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. As she sinks through the cracks, she becomes one with her commemoration, merging with the legacy she was so desperate to reclaim.

HOW IT COULD BE BETTER?

You might wonder who I am to critique a celebrated screenplay like this one. But keep in mind that no screenplay is perfect, and script notes are often rooted in subjective tastes rather than objective criticisms. Since THE SUBSTANCE adheres closely to structural conventions, my comments will mainly focus on enhancing execution rather than overhauling the overall structure.

I would suggest inverting the Debate section so that Elisabeth is initially intrigued by the process, but her interest is halted by the suspicious lack of credentials and the shabbiness of the Supplier’s facility. After returning home, she feels disillusioned with her life, and it’s only when she witnesses the world moving on without her that she begins to reconsider. This shift could make her decision more believable, allowing us to linger in her current reality a bit longer. It would help us better understand her struggle and why this dubious choice might seem appealing - something that feels illogical in the current draft. We are well versed with the hero’s journey and this debate section can feel like a formality, but put yourself in Elisabeth’s shoes; I would try several avenues before resorting to this mysterious method that nobody has ever heard of. Cosmetic surgery, Eastern medicine - hell, just about anything seems preferable to giving my address to a faceless stranger and then injecting myself with green goop without medical supervision.

In my opinion, Act 2A is likely the weakest of the three acts. While there's some satisfaction in watching Sue succeed and it's clear that this puts her and Elisabeth on a collision course, very little actually happens between pages 25 and 60. The biggest progression is Sue acing her first audition and landing the show, which unfolds without any significant obstacles. Meanwhile, Elisabeth seems to fade into the background during this act.

If Elisabeth and Sue continue to operate as a single entity from their initial mitosis until closer to the midpoint, then Sue’s decision to carve out her own identity by taking the name ‘Sue’ could become a pivotal turning point. My main concern with Elisabeth’s role in 2A is that we never really see her and Sue as the same character. By tweaking this dynamic, we could better illustrate Elisabeth’s feelings of betrayal by her younger, more successful self. This approach would enhance her internal struggle, allowing the audience to feel her shared sense of achievement for Sue’s actions while simultaneously demoting her position.

Personally, I find the choice to make the New Year’s Show the climax a bit confusing. For Elisabeth, the pinnacle of her career was acting and winning an Oscar, which represented the perfect blend of skill, beauty, and attention - everything she desires. On the other hand, for Sue, her journey starts with the dance show, and she quickly graduates to hosting this live event, which boasts fifty million viewers. Plus, we hear that she’s landed the cover of Vogue and secured a role in an upcoming film with an exciting director. Both of these achievements feel more significant and aligned with Elisabeth’s dreams, especially since she’s always yearned to be on screen.

Sue’s comment about putting on shows for her family as a child feels out of place, considering she didn’t really have a childhood of her own—only second hand experiences from Elisabeth. While the New Year’s Show provides a bombastic, in-person climax for the narrative, if it’s meant to culminate in this event, Fargeat could have strengthened the justification by indicating that Elisabeth always dreamed of hosting the New Year’s Show. It might also help to suggest that she was overlooked in favor of younger talents, making this event even more meaningful for her character arc. The current version seems occasionally uncertain if it wants the audience to think of Sue and Elisabeth as two sides of the same coin, or two unique individuals.

There are two ‘dream sequences’ in the film (three in the screenplay, though one of them is left ambiguous in the theatrical release). In both the scene where Sue’s catsuit zipper releases her organs and the scene where she pulls a drumstick from her navel, we become invested, only to feel disappointed by the fake-outs. Both events seem like they could have dire consequences and advance the plot, but they ultimately turn out to be contrivances.

The ‘but it was just a dream’ technique is one that young writers are often warned against due to its overuse as a narrative shortcut. When it appears repeatedly, it disconnects the audience. Fool me once, shame on you; but when I’ve been fooled twice, I find it hard to fully engage with subsequent scenes because I start doubting their legitimacy. This kind of repetition can undermine the tension and emotional stakes, making it difficult for viewers to invest in the story as a whole. In a screenplay that might be accused of being too on the nose at times, this technique manages to feel like one step too far.

The filmmakers must be fans of Return of the King because there are multiple points in the third act that could easily qualify as the conclusion, only for another scene to fade in. You want your finale to feel like it passes through the eye of a needle, bringing everything together into one streamlined plot thread. Instead, this last ten to fifteen minutes feels more like a frayed knot, with threads sticking out all over the place. While that chaotic energy suits the film in a way, a more concise ending could help it stick the landing a little smoother. A tighter conclusion might enhance the overall impact, leaving the audience with a stronger sense of closure. The conclusion goes too far - but wait… so does Elisabeth.

LESSON FROM THE SCREENPLAY

Fargeat shows incredible restraint by omitting a prologue that explains what happens to a person when they take the Substance, even though this is visually foreshadowed in the cold open. By keeping Elisabeth from having a face-to-face with the Supplier, she misses the chance to ask a ton of questions about how the process works or to hear any testimonies. As a result, when Elisabeth ‘births’ Sue, we go into that scene with no prior knowledge of how it will unfold, what it will look like, or what the consequences will be. Experiencing this through Elisabeth’s POV means we share her discovery, her horror, and the subsequent confusion.

This technique teaches us the value of reducing precursors and set-up scenes, letting the audience be fully absorbed by the events as they unfold. It creates a more visceral experience, delivering shocks without any undue warning, which can make the narrative all the more impactful.

WHICH IS BETTER, THE SCREENPLAY OR THE MOVIE?

As Fargeat both wrote and directed the film, there is less difference between the two products than one might typically expect. The primary job of a screenplay is to be a blueprint for the director, who may have ideas or interpretations of their own. When these are one and the same, there is less contradiction between these two auteur positions - though there are still differences between the screenplay and film.

The original screenplay is atypical in many ways - informal in formatting, in how dialogue is delivered, and with incredibly heavy emphasis on sound, stage direction, and internal dialogues - almost like a novel in parts. As Fargeat wrote this to direct herself, this is more admissible than if she was writing for someone else. Let’s take a look at some examples.

In the above example, an advertisement or introductory video plays, promoting the Substance. In this case, the dialogue is presented through dialogue (in bold) present on action lines rather than through classic dialogue windows with narrower margins. This gives it a more authoritarian, surgical appearance - almost like a prescription label - and provides an example of Fargeat’s willingness to bend convention in favor of tone.

In this excerpt, taken from the ‘birthing’ scene - Fargeat breaks conventions by presenting short, segmented images and sounds instead of a standard scene format. She plays with the size of the font, adding in bold text, and formats what could have been ‘A LONG BEAT’ to eight lines, emphasizing the length of this silence.

In this example, Fargeat pushes the boundaries of format convention even further, messing with font size and format to the point that lines clip into one another. This is designed to convey Elisabeth’s chaotic, shattered state of mind at this point in the screenplay.

A director’s fingerprints are typically more visible on a film than a screenwriter’s on the script - due to the plethora of influences the former has: casting, cinematography, color grading, audio cues, etc. Fargeat ensures her screenplay is dripping with personality, where it would be immediately identifiable as her own work on the page, and will surely be emulated in years to come by writers aspiring to mimic this style.

In this reader’s opinion, the screenplay ekes out the film for one major reason - the imagination can conjure up more vivid and believable images than prosthetics and VFX ever can. While the latter half of the screenplay escalates the body horror angle in horrific new ways, the film doesn’t manage to have the same impact due to (intentionally) larger than life performances that border on hammy, and effects which are occasionally grandiose. While the reader can condense the satirical elements with the real, gruesome, medical aspects of the screenplay - the visual distinction on screen leaves the viewer unsure what we’re supposed to take seriously or otherwise. While both can be true, the adjustment period may take the viewer out of scenes while the screenplay allows for more commitment.

CHANGES FROM SCREENPLAY TO SCREEN

As mentioned above, Fargeat wrote and directed, carrying over the clear image she had for the film from page to screen. As such, there are only minor changes between the products.

In the film, the Walk of Fame star imagery was deemed insufficient to establish the tone as that of a dark fairytale, going so far as to bury the star under thick snow (pretty atypical for Hollywood Boulevard), heralding the winter of Elisabeth’s career. While the wording of the screenplay lays this on pretty thickly, sometimes additional imagery is required to convey the same message.

One of the more significant changes presented - the film cuts out Craig Silver, Elisabeth’s former agent and Sue’s prospective new manager. It could be argued that he and Harvey, the network director, fill much of the same niche - and Harvey is dialed up to eleven in the final product to combine their purposes. In this regard, Harvey becomes the only character in the film to make any negative comments about her appearance - highlighting the power that a single negative comment can have on one’s self-perception.

In the film, the period of regained control after Elisabeth calls the Supplier and accepts the trial of the Substance is muddied, she continues to suffer from a period of hesitation during this section. This is likely a more realistic decision, as she still knows nothing about how the product works, the side effects, or the associated risks. The decision marks a step toward proactivity rather than passivity, but she has still yet to commit without hesitation.

Fred, the once-classmate of Elisabeth, who maintains interest in her when nobody else does, never returns in person in the film. Conversely, during the climax - seconds before Elisabeth terminates Sue - she runs into him. He asks why she’s been avoiding his calls after ghosting her on their date (which she proposed). This felt like an important scene in the screenplay, as he doesn’t treat her any different even in her deteriorated state. Elisabeth seems more uncomfortable being spotted by anyone else than Fred during their interaction - as though she continues to take his adoration for granted, or his attention is insufficient because of her lowly opinion of him. This has been axed in the theatrical release, presumably for pacing and momentum, allowing Elisabeth to follow through with the termination of Sue without giving her the opportunity to second guess herself.