How to Read a Script: A Beginner's Guide

Hey there, fellow film enthusiasts!

Are you a beginner itching to dive into the world of screenplay reading, or more specifically, learn how to read a film or TV script? Whether you're curious about your buddy's latest script, stumbled upon something intriguing on Kinolime, or can't wait to read the screenplay of Scorsese's newest masterpiece before it hits the big screen, you're in the right place.

Script reading is a vital part of film appreciation, if you’re an enthusiast or a fully-blow professional.

First things first, the initial challenge of a script reader is to figure out what tickles your fancy. Got it? Great! Make sure it's easily accessible online and hit that download button. Settle into your coziest chair (you might be there awhile if it's a feature film), grab your favorite beverage, and keep a notepad or a blank document ready. Now that you've chosen your script, let's delve into how to read a screenplay effectively. You're all set for an enlightening read!

So What Exactly is a Screenplay?

A screenplay is less like a novel and more like a basic blueprint for the entire film crew. Think of it as a guide for actors, directors, location scouts, and even the directors of photography. It's not just a story; it's the skeleton of the film-to-be.

Title Page aka What am I Looking At?

Okay, so you've got the script in front of you (right side up, I hope). The first thing you'll see is the TITLE PAGE. This is the front door to a new world. It lists the title, the writer(s)' names, the draft number, the completion date, and often the contact info of the writer or distributor.

But wait, what's this? You downloaded 'The Dark Knight', and it says 'Rory’s First Kiss'? No panic! Movies often have these cool 'working titles' to keep their real identity under wraps. Like how 'Star Wars' (1977) was 'Blue Harvest'. Or the hilarious 'Teenage Sex Comedy That Can Be Made For Under $10 Million That Your Reader Will Love But The Executive Will Hate' for 'American Pie' (1999).

Confused about 'Schindler’s List' saying it’s written by Thomas Keneally and Steven Zaillian and not Spielberg? Here's a little insider info: films aren’t always the brainchild of their directors. Shocking, right? In the film world, the director is often the last piece of the puzzle. Like with 'Schindler’s List' (1994), Spielberg worked his magic on an already brilliant script. It’s all about teamwork in Tinseltown!

How Many Pages Are We Talking?

When you read screenplays, you'll notice a variety of lengths depending on the genre. So, you’re browsing around and find the movie or show you want to read. Awesome… but you’re a little confused on page lengths. Some are 92 pages, while others are 140? Script lengths are a bit of a wild ride. There is a rule of thumb that states one page equals about one minute of screen time.

For a feature film, aim for the sweet spot between 90 and 120 pages. Below 90? A little too short… Over 120? You might start wondering when the credits will roll. For TV pilots, the game changes a bit. Comedy or sitcom? Think 25 to 35 pages. For drama or sci-fi, typically designed for an hour-long slot, about 50 to 60 pages is your target.

But What About Those Thick Scripts?

Hold on, you found Oppenheimer's script and it's a whopping 197 pages? When you're a box-office titan, rules can be... more like guidelines. If you're not yet a Hollywood big shot, better keep that script lean.

But This One is Super Thin…

You must have found 'The Artist' and 'Mad Max: Fury Road’. Both Oscar darlings and both around 40 pages? Ah, the beauty of cinema! Silent films like 'The Artist' (2011) and dialogue-sparse, action-packed thrillers like 'Mad Max: Fury Road' (2015) dance to a different beat. Dialogue typically bulks up a script. But in these films, actions speak louder than words, literally, so the page count drops.

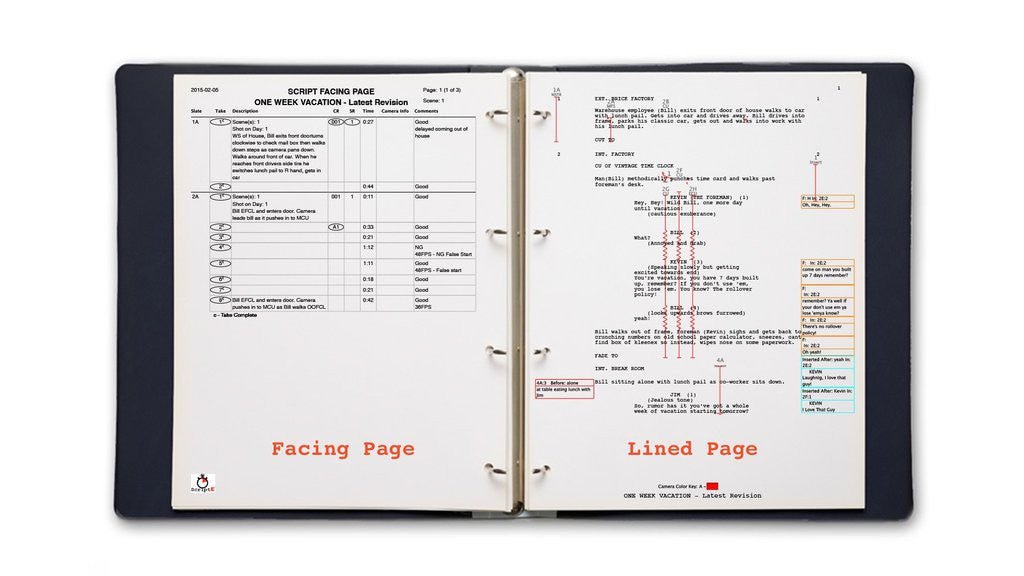

There’s Something Called a Shooting Script...

One last thing – shooting scripts. These are like the Swiss Army knives of scripts. They're packed with alternate scenes, extra dialogue, and various versions of events, giving the production team plenty of options. This means you might find two pages of script translating to just thirty seconds on screen.

So, whether you're dissecting a lean indie script or marveling at a blockbuster behemoth, remember: the length of a script is part of its unique story.

What Draft Should I Read?

As a general rule of thumb, read the latest version of the draft. If you’re more interested in learning about how the story evolved through the development process, I like to read the first draft of my favorite movies.

Basic Structure of a Screenplay

While it may seem like there are more rules than necessary, the screenplay format is set in stone – and has been since before any of us were alive. Based on the stage play format, they have a very strict set of rules. The discerning eye will notice if anything is amiss in a second. If you’re a script writer, don’t worry – your software should do this for you. But if you’re a reader, ensure basic uniformity; a monospace Courier font, single-spaced, 12-point size. Also check that the top and bottom of each page allows a 1-inch margin, as should the right-hand margin. The left-hand margin sometimes extends from an inch to an inch and a half to allow for a hole punch when printed.

Before we dive into the art of screenplay reading, let's familiarize ourselves with some essential scriptwriting terminology. Understanding these terms is crucial for interpreting and appreciating the nuances of a screenplay.

Shot Heading

Shot Heading (or ‘sluglines’): This is the first line of a new scene, indicating whether it's inside (INT.) or outside (EXT.), the location, and the time of day. For example, "INT. KINOLIME OFFICES – NIGHT" tells us the scene occurs indoors at the Kinolime offices during nighttime. Sluglines help the production team plan the logistics of filming.

Direction

Direction (or ‘action lines’): These lines describe what's happening visually in a scene. Direction can include descriptions of settings, characters, and their physical actions. They're written in the present tense and aim to create a vivid, visual picture of the scene. For example, “MEARA (27) works at his desk, brow furrowed, illuminated by his computer screen. Somewhere nearby, a JANITOR vacuums.”

Character Names

Characters: Note that MEARA and JANITOR are presented in all caps, which is common practice when introducing a character for the first time. If Meara doesn’t show up again until Act Three, you might forget him. But if he’s not in caps at that stage, you’ve met him before. Age, and sometimes physical attributes, appear in brackets if pertinent. Use sparingly and only where necessary. “MEARA (27, five foot seven but tells people he’s five foot eight, broad, prematurely greying at the temple).” That’s a little too much information and cuts close to the bone.

Dialogue

Dialogue: This refers to the words spoken by characters in the script. Dialogue is crucial for revealing character traits, advancing the plot, and conveying emotions. In a screenplay, the character's name appears in all caps above their dialogue lines. For instance:

JANITOR (O.S)

Help! Aghhhhhhh!

MEARA

(nervous)

Where are you? What’s going on? Am I really

greying at the temple?

Parentheticals

Parentheticals: These are brief descriptions placed between the character name and the dialogue to describe how a line should be delivered or to provide essential action cues. Parentheticals are used only when necessary to clarify the dialogue. For example, in the above dialogue, "(nervous)" is a parenthetical, indicating Meara's emotional state as he speaks.

Understanding these fundamental screenplay elements will greatly enhance your script-reading experience, allowing you to visualize the story as it would appear on screen.

Understanding Script Terms

There are countless script terms and industry lingo, and this article would be endless if we included them all. Here’s a rapid fire round of some tips for the most common examples.

FADE IN: Often used at the genesis, this suggests that the picture eases in from a black screen rather than appearing suddenly.

FADE OUT: Fade to black, to ease transitions between scenes.

CUT TO: This suggests the scene ends, possibly abruptly, and we’re catapulted into the next scene.

VOICE OVER (V.O): This is dialogue that is untethered from anybody in the scene, such as narration or an internal monologue.

PRE-LAP: This dialogue belongs in the subsequent scene, but we’re getting a preview before the scene starts.

The Art of Reading a Screenplay

First Reading

The initial reading is just that – you sit and read from FADE IN: all the way to ROLL CREDITS. Try and accomplish this in one sitting if at all possible, it will help with the pacing. If you’re like me and struggle with names, jot down a mini-cast list. Like, JOHN (39) – sewage treatment expert or ALISON (62) – trapeze artist. It’s a lifesaver for keeping track of who’s who.

Once you’ve read the entire thing, take down any initial notes, questions, or concerns you have ahead of your second read.

Second Reading

Often, the second read will ensure you catch things you missed the first time – subtle hints, foreshadowing, that sort of stuff. It’s like rewatching a great movie and noticing all the clever little details. Reference your questions from the initial reading here, to see if you can answer any of your own questions. Maybe the Butler offers some cryptic advice that helps tie the whole thing together in your head.

Here's a tip. On this pass, take your time. Analyze everything – character’s development, their arc, their language, how their motivations ebb and flow. Relationships, how they blossom and wilt, where they work best, and when they feel forced. How the basic premise is executed.

The purpose of this read is to be discerning, critical, analytical. Don’t let anything slip past your examination.

Comparative and Contextual Analysis

As a script reader, it helps your analysis if you can identify tropes, cliches, references, or homages within writing. If your chosen script is a detective noir, it’s beneficial to have some knowledge of the genre. Compare it to the successful writing in that field, see how it holds up. Once you’ve twice read the entire script, you should have a clear image in your mind, allowing you to compare and contrast.

If the script takes place in a historical setting, or is based on real-life events, consider how this narrative retelling is different to a documentary presentation. What does the writer have to contribute, what is their comment on these events?

If you are familiar with the writer’s body of work, collate the work against past writing. Does the author expand on themes they previously explored? Is this a superior examination?

The Significance of Scene Descriptions

Scene descriptions should go beyond just describing the visuals, they should dictate the mood and premise of the scene. Pay careful attention to the language and subtext of the action, identify the emotion that the writer is trying to elicit.

Check out this climactic scene from Zodiac, written by James Vanderbilt.

Note the clipped sentences, suggesting the tension. This is descriptive of the location, slowing the scene down and heightening the tension. This would not work so effectively in, say, an action scene – where the goal is to whizz through and increase the tempo.

Deciphering Dialogue

Dialogue is magical, in that sometimes what’s left unsaid is just as important as what is said. Read dialogue carefully, consider the language and how the words could be interpreted in various ways.

Remember – actions speak louder than words – so if your character repeatedly insists they’re a pacifist in conversation, but their actions defy this, they’re always looking for a fight – what should you really believe?

Always pay attention to the character’s name, as skipping over these may result in misattributing dialogue and confusing your reading.

Analyze this scene from Die Hard, in which villain Hans speaks with his hostage Mr. Takagi. What do we understand about their relationship?

Despite having Takagi captive, Hans makes relaxed comments about his clothing. This gives him an aura of authority in the relationship, while ensuring Takagi knows that he has the situation under control. It also humanizes him, putting him on the same level as his hostage. Finally, it shows that Hans has done his research – this isn’t a heat of passion stick-up attempt. Knowing Takagi’s tailor means that he’s likely privy to other personal details that could threaten Takagi.

Story Structure and Pacing

Another component to think about when reading a screenplay is the structure and pace. Think of pacing like the heartbeat of your script – it keeps everything alive and kicking. It's what glues you to your seat, popcorn forgotten, as you flip through the pages or watch the story unfold on screen.

But if the pacing's off, it's like hitting speed bumps on a highway, or worse, getting stuck in a traffic jam. Moments that drag on forever or scenes that zip by too quickly can throw off the whole experience.

So, how can you tell if a script's pacing is off? Trust your gut. It's like developing a sixth sense – the more you read, the better you'll get at sensing these things.

Now structure. Imagine you’re reading a 100-page script. A classic breakdown would be three acts: the first 25 pages (Act One), the next 50 pages (Act Two), and the final 25 pages (Act Three). This isn’t set in stone, but it’s a tried-and-true structure for crafting a story that keeps viewers hooked.

Check for shifts in tone, objectives, or locations at these act breaks. It’s all about keeping the audience on their toes with fresh twists and escalating stakes.

Now, let's switch channels to TV. The act structure here is more flexible. Take a 30-minute show like 'The Simpsons' – it sticks to a three-act structure similar to films: setup, confrontation, resolution. But when you step into the world of hour-long dramas like 'Breaking Bad', you're looking at a more complex, five-act structure. And some shows? They make their own rules.

The bottom line is engagement, coherence, and progression. Whether it's the plot thickening or characters evolving, these elements need to be in sync to make the script a page-turner. If they are, you've got a winner on your hands.

Pacing is the pulse of storytelling – it's what makes the difference between a good script and a great one. Keep this in mind as you continue exploring the art of screenplay reading, and you'll soon develop an instinct for what makes a script truly captivating.

Reading Between the Lines

Analyze beyond the page – try to identify recurring motifs, themes, and development that’s subtle or deft. Much of a writer’s intent will not be explicitly stated.

In the Wachowski Sister’s ‘The Matrix’, what could the prison represent, and how can we know? We can’t know for certain without asking the writer(s) directly – but searching for parallels and projecting our own opinions onto situations allow the writing to feel personal and lived in.

The Role of Screen Directions

Screen directions are there to guide actors and directors, sometimes in lieu of dialogue. These can be tiny things – a shift in weight, a second of eye contact – or more tangible – hand gestures, body language. Analyze how this impacts the writing and tone. Pay attention to directions as well as dialogue.

In Spike Jonze’s Her, this scene sees Amy show her partner Charles and friend Theodore a documentary clip of her mother sleeping. This is tedious and uninteresting subject matter, and the beat where they expect something to occur is awkward and drawn out. This creates discomfort for both Amy and her audience, as well as the reader.

Tips for Script Analysis Exercises

How can we improve our script analysis?

Scene Rewriting

If a scene isn’t working, identify why. Try rewriting it! Is it too long, slowing down the pacing? Chop what you can and see if it works in an abridged format. Does it fly by too quickly? Slow it down with direction and dialogue. Is the tone all wrong? Cut the jokes and see if you feel it serves the characters better.

Every scene should have a purpose. Ensuring that the writing services that purpose as a jigsaw piece of the entire narrative is imperative to good storytelling.

Character Role-Playing

Try honing in on a single character, putting yourself in their shoes. Try reading just their parts aloud, delivering their dialogue in various ways. Understand their motivations, sample a scene toward the beginning and end, then contrast their emotional and developmental state in both. This will help you analyze their language and relationships.

This may seem silly, but role-playing is a core aspect of storytelling!

Outline Reconstruction

Try boiling the plot down into a synopsis, or logline, then building it back up from memory. What parts were expelled? They’re likely the least interesting aspects, or at least the most forgettable.

Attempt to fit the plot into a plot framework, see if the act breaks line up, and how tweaking this may impact the pacing.

Discussion Groups

As screenwriting becomes increasingly accessible, so does the number of interested parties. Find a discussion group, online or in person, where likeminded script readers can contribute to your insights. Together you can read movie scripts, discuss premises, share tips, secrets, and coverage for one another. This will help you develop your own voice by sharing with others. Everyone has their own technique to share!

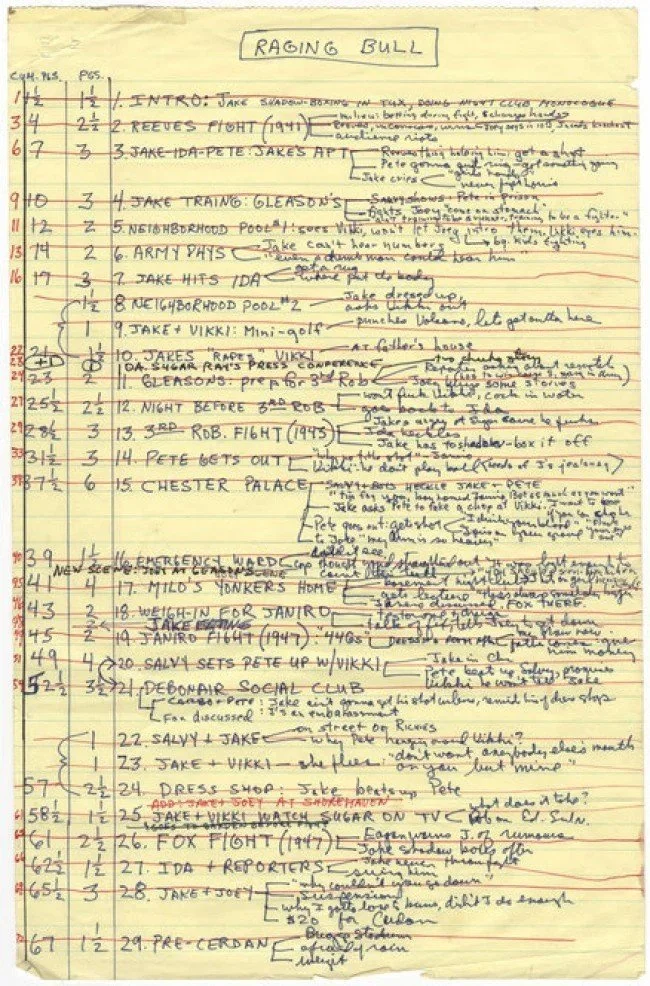

When You Don’t Like a Character

Now, what if a character rubs you the wrong way? That doesn’t automatically mean they’re poorly written. Some of the most fascinating characters are those we love to hate. Think Jake LaMotta in 'Raging Bull', Lou Bloom in 'Nightcrawler', or even Ross Geller from 'FRIENDS'. They’re flawed, sometimes morally dubious, but they’re compelling.

A protagonist should tick at least two boxes: competent, likeable, or proactive. Hit two, and you've got a character that pulls the reader in. Miss the mark, and the character might fall flat.

When You Strike Gold

Stumbled upon a script that blew your mind? Fantastic! Spread the word and learn from it, but don’t get too starry-eyed. Even a masterpiece can have room for improvement. And remember, just because this one's a knockout doesn't mean the next good script is any less valuable. Each script is its own universe – treat it that way.

Beyond the Last Page: Engaging with Screenplays

CONCLUSION: promote KINOLIME here.