Building Your Story World Without Overwriting

Worldbuilding is a term used to describe the idea of creating a story location/world/universe that is somehow different from our own. In Tolkien, it was Middle Earth and beyond, where hobbits, orcs, and elves dwelled. In screenwriting, most of our worldbuilding is done outside of the script itself; from there, we must use a discipline of restraint to introduce readers to the laws of the universe in which our story takes place.

There’s a phrase “show, don’t tell” that is very popular for screenwriters. This is because worldbuilding in film is best experienced, not explained. Too much exposition feels clunky; overwriting weakens the immersion and pacing of a great story. Strong story worlds feel lived-in without being spelled out.

This isn’t always easy to do. It requires patience, trusting in the world you’ve built and allowing it to unfold naturally and in a satisfying way. Let’s talk about how to achieve that.

What Worldbuilding Means in Film

In cinematic worldbuilding, that is, worldbuilding for film specifically as opposed to novels or games - the universe reveals itself through visuals, behaviors, and context. Sure, there may be times when some exposition is helpful (for example, Obi-Wan Kenobi explaining to Luke Skywalker that the Force is an energy field created by all living things that surrounds, penetrates, and binds the galaxy together.

But before that, we learned a lot about George Lucas’ galaxy far, far away from watching the film: the production design of the rebel ship and the costumes of the imperial and rebel forces, the desert planet with advanced droid technology, the dual opinions of the Empire as seen from Princess Leia’s perspective as a now captive and from a young farmboy who dreams of joining the military and flying somewhere new.

The role of the screenwriter is to find the most subtle and intuitive ways to convey those “rules” or the world; it’s much more important to tell the story of the people living in the world, not how the world itself works.

To this end, avoid lore dumps, focus on how characters move through their environment and how the lore impacts them, and emphasize the cause-and-effect inside the world.

What to Show vs. What to Hint

Screenwriters are encouraged to understand narrative economy; again, you’re not writing a novel. You’re writing a screenplay. It is the blueprint of a visual cinematic film or television series. All clues must be seen, heard, or experienced.

To do this, you want to show things like behavior, consequences, routines, and power dynamics. Think of the differences between Hobbiton and Rivendale; from their architecture alone, we can see that hobbits are a simple folk living closely attuned to the earth, from the homes they carve into hillsides to the gardens they keep. Meanwhile, elves have built ancient and lustrous palaces, which they defend with supernatural speed and grace. They are grandiose and powerful.

There are ways you can hint at the backstories of your world, including politics, history, and mythology. In Game of Thrones, characters weren’t reading from bibles to inform the audience that there was a pantheon of beliefs; they were uttering prayers to “the old gods and the new” or burning effigies for the lord of light. Their religion was in their speech, just as in our world, people might “swear to god” when making a threat.

The audience doesn’t need full answers for everything, just coherence. Let relationships imply history. Let rules be revealed through conflict or mistakes to build tension and ignite forward momentum. Let the world push back on your characters.

If the audience understands the stakes, the world is working.

Sensory Cues for Film

Be deliberate about grounding your worldbuilding in the senses, not the screenplay exposition. What are the characters experiencing from their environments? What do they see? What is the architecture of their world and why is it important? Does their environment elicit physical discomfort or danger? Or is it the opposite, and they are pampered and safe (until they’re not)?

In sensory storytelling for film, these clues should be selective, not exhaustive. Remember, one strong detail is more effective than many weak ones. Katniss Everdeen had to sneak outside into the woods to hunt for food for her family because the government starved her people. The politics were slowly revealed, but the concept was introduced when we saw a young girl with her bow and arrow in the woods. These visual storytelling techniques built the foundation for the reaping and story to follow.

Common Pitfalls

There are screenwriting mistakes you want to avoid with some simple film worldbuilding tips. It can be tempting to over-explain the rules of the world but trust that your audience is smart; they will pick up on subtext and the clues you offer. It can be helpful to have characters address certain aspects of the world through conversation, but beware of dialogue that exists only for the sake of exposition.

Here are a few pitfalls to avoid:

Over-explaining rules of the world": It can be helpful to begin with an opening chyron (or in Lucas’ case, a scroll) or voiceover narration to give some context, but you get about three sentences before you’ve overloaded your audience. Give the audience what they immediately need to know to jump into your character introductions, then let your subtext take over from there.

Front-loading information in early scenes: Just as you should avoid over-explaining, you also need to resist the temptation to front-load information at the beginning of your screenplay. Introduce your world breadcrumb by breadcrumb so your audience will hunger for more and follow the trail you’re laying through your story.

Characters saying things they already know: “As you know, when we were growing up, our parents were hard on us.” If your characters are beginning their dialogue with “as you know,” it’s very likely that it will feel disingenuous to the audience because humans don’t actually talk like that. “You’re my baby brother! I gotta take care of you!” Again, it’s pretty rare to define relationships verbally like that. You don’t have to make the characters explicitly state out loud who they are to one another; it’s more compelling if you reveal it through how they interact with one another. Siblings might not actually call one another “brother” or “sister” but they’ll talk about “mom and dad.”

Confusing complexity with depth: Just because you have created a deep, rich world and backstory doesn’t mean that the audience needs to know every single detail. For thirty years, audiences accepted that the Force was some kind of energy that could be felt and drawn upon; in Episode I, the idea of midi-chlorians was introduced, microscopic, intelligence life forms that resided within the cells of living organisms and allowed the Force to speak through them to their hosts. You don’t have to be a Star Wars fan to be scratching your head at this; and if you are a fan, well, then you probably already know that this is complexity that was unnecessary and potentially distracting.

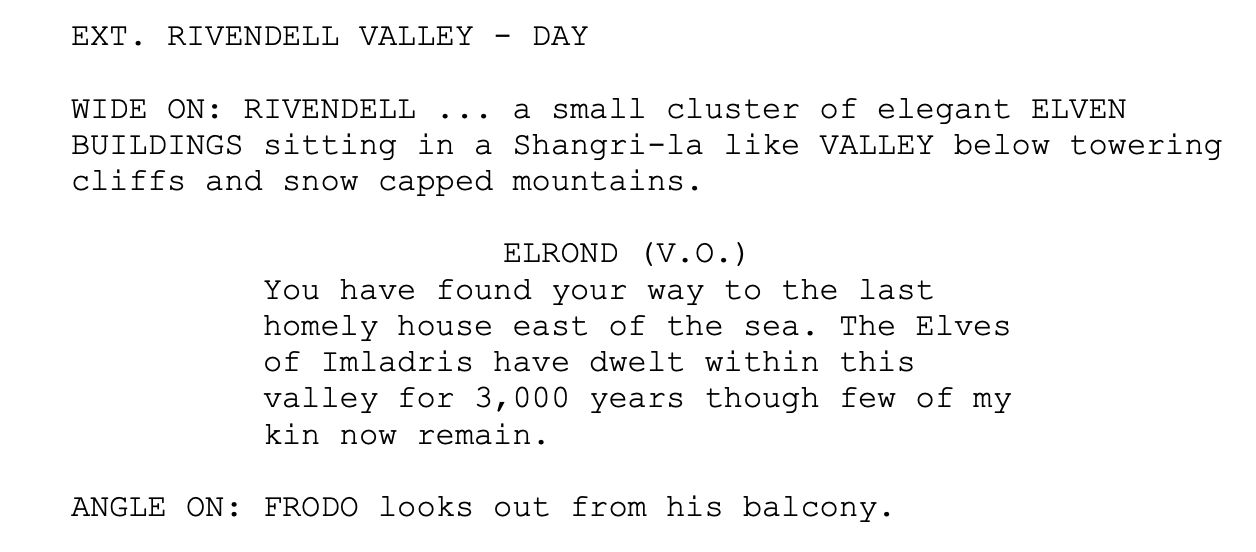

Writing for the page instead of the screen: Remember, you’re not writing a novel; you’re writing a screenplay. You don’t need to go into the detail of how you imagine a building to look - you just need to give the reader important information. Consider Peter Jackson’s description of Rivendell, including the action line describing the valley and Elrond’s words:

It’s decidedly shorter than the many lyrical descriptions in Tolkien’s novel: “Frodo was now safe in the Last Homely House east of the Sea. That house was, as Bilbo had long ago reported, ‘a perfect house, whether you liked food or sleep or telling or singing, or just sitting and thinking best, or a pleasant mixture of them all.’

A great tip to try is to identify your explanatory dialogue, omit it, give the pages to a reader, and see what still works or where there is confusion. Look for opportunities to imply something visually rather than with clunky dialogue. Overall, trust your audience’s ability to connect the dots.

Conclusion

Remember, restraint is your creative strength. Pay attention to how great projects achieved their worldbuilding. When was something verbally explained well? When was it overwrought? Be deliberate about when you choose to reveal information to the audience and to the characters. Mystery increases immersion and a strong story world feels complete, even when partially unseen. All of your hard work imagining and worldbuilding should serve character and conflict, not overshadow them.