Cabaret – A Flawed but Timeless Movie Musical

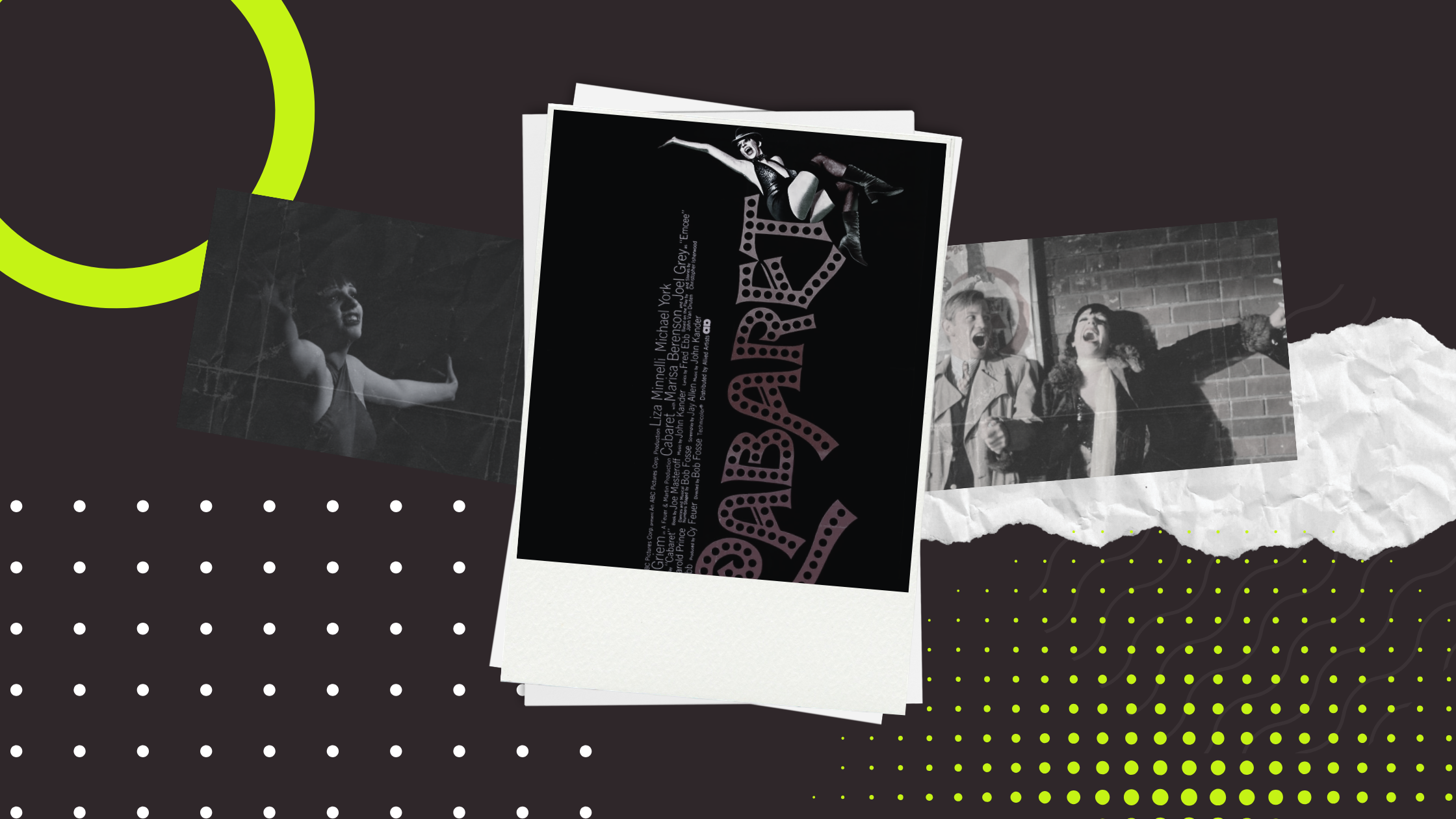

Cabaret has long endured as a cultural classic— sustained by decades of revivals on and off Broadway, its seductive, glamorous aesthetic echoes through works like Rocky Horror, Moulin Rouge, and Burlesque while its political urgency remains strikingly relevant. Before becoming a musical phenomenon, Cabaret began as I Am a Camera, a London stage play adapted from Christopher Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin. A 1955 film followed, before the story was reimagined and renamed as a Broadway musical in 1966.

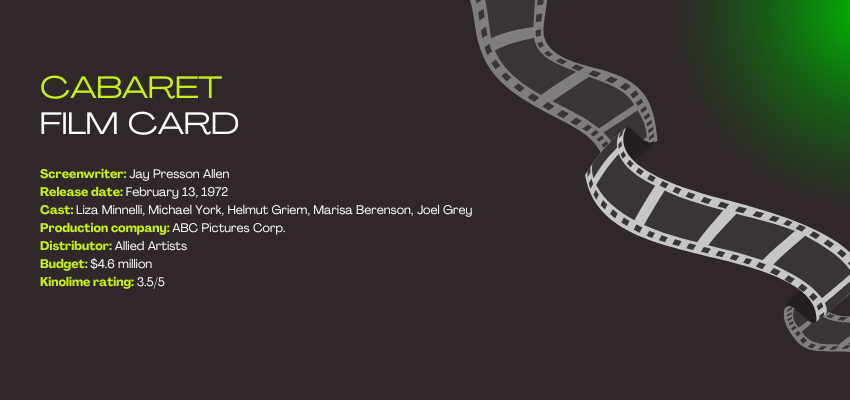

That production was a direct forerunner for Bob Fosse’s 1972 film, starring Liza Minnelli as Sally Bowles and Joel Grey as the Emcee. The film won eight Academy Awards, laying the groundwork for Cabaret’s lasting influence. Its original musical additions of “Money, Money,” “Maybe This Time,” and “Mein Herr” are now inseparable from the show despite later stage revivals somewhat controversially altering the placement of some numbers.

In short, Cabaret (1972) is undeniably influential, but influence alone does not guarantee greatness. Is it the most effective way to experience this story, or have later stage productions surpassed it in narrative power? As someone deeply invested in Cabaret across its many forms, I aim to examine what the screenplay achieves, and where it falls short of the greatness the material demands.

OPENING IMAGE

Before Cabaret offers any visual spectacle, it introduces its world through sound. Overlapping chatter, clinking dishes, and the unfocused tuning of an orchestra replace conventional music, evoking the restless murmur of an audience awaiting a performance. As the opening credits play over a black screen, this soundscape gradually swells, immersing the viewer into the Kit Kat Klub alongside the club’s patrons in shared anticipation.

This approach reflects Cabaret’s ongoing effort – on stage and screen – to gently fracture the fourth wall. By positioning the viewer as part of the audience within the narrative, the work signals that the performance is not merely for us, but about us.

The credits end with a titillating drumroll and cymbal crash, giving way to a musical vamp. The first image is a close-up of the Emcee’s heavily made-up face, seen in reflective glass. He smiles directly at the camera with wide, doll-like eyes and a painted smile. “Wilkommen, bienvenue, welcome,” he sings, beginning the opening number by inviting the audience in.

The effect is immediately immersive. From the outset, the film draws us inside the Kit Kat Klub, positioning us not as distant observers but as fellow guests, seated among the wealthy and colorful front-row patrons rather than behind the perspective barrier of fiction.

SET UP

As the Emcee continues the club’s welcome, we intermittently cut to our protagonist Brian, newly arrived in Berlin by train. The perspective periodically flips back and forth from Brian’s experience to the Kit Kat Club, establishing two aspects of the setup simultaneously. In the film, this sequence departs sharply from the original screenplay, adopting a faster pace that omits several scenes which, in my view, would have strengthened the narrative (I will be going off the screenplay rather than the final cut). This, sadly, marks the first of my frustrations with the adaptation.

Inside the Kit Kat Klub, the film quickly establishes a spectacle of decadent provocation, animated by an unconventional crowd. The performances are incredibly raunchy, and both the club’s entertainers and patrons are unmistakably queer. At the time, LGBTQ+ figures in mainstream cinema were often framed as sensational novelties, their visibility tied to shock value (ex. Rocky Horror’s Dr. Frank n Furter, inspired by the Emcee). Cabaret participates in this heightened portrayal, featuring several visibly queer members of the ensemble in accordance with its image of depravity. However, this depiction is also grounded in historical reality. The Kit Kat Klub embodies the vibrant nightlife of Weimar-era Berlin, which was notably liberal and attracted such figures before Hitler’s rise ushered in a punitive conservatism that would condemn such excess.

A subtle foreshadowing is established when a young Nazi boy crosses paths with a Salvation Army girl at the door to the club, both with the innocent enough purpose of collecting donations from wealthy patrons. The boy is paid little mind by any of the clubgoers, his foreboding allegiance dictated only by his armband. He is swiftly expelled by the manager for siphoning possible tips from deep pockets and leaves without resistance, but as a harbinger of impending catastrophe.

INCITING INCIDENT

In the screenplay, the inciting incident arrives early, tightly interwoven with the setup. The original scene is omitted from the film, and is replaced with Brian’s first meeting with Sally Bowles. I emphasize this because I actually believe the scene from the original sequence better suits the narrative.

Brian at this point is still on the train, freshly docked at the station. A reserved but polite young man, and fluent in German, he strikes up a mildly awkward but friendly exchange with a fellow passenger, Ludwig, after helping the shorter man retrieve his luggage. Warm and eager to assist, Ludwig refers Brian to what he verbally dubs the “finest rooms in Berlin” and welcomes Brian to the city. This subtle recommendation puts Brian on a collision course with the Kit Kat Klub, Sally Bowles, et al, and from this moment, Brian becomes witness and participant in the intimate dramas that define his fateful stay in Berlin.

Brian functions as a deliberately passive protagonist – more lens than hero. Echoing Christopher Isherwood’s role as observer, and the original title I Am a Camera, Brian exists primarily to watch and record. Cabaret is less invested in his inner transformation than in the national unraveling he witnesses, as fascism slowly permeates Berlin during his stay. Accordingly, the inciting incident is understated rather than grand: not the launch of a heroic quest, but the moment the camera is steadied and begins to run.

DEBATE

Brian forms a fast friendship with his new fellow tenant Sally Bowles, a charming young American woman with atrocious German and grand dreams of being a movie star. At the moment, her stage is the Kit Kat Klub’s cabaret, which Brian begins visiting regularly to watch her perform amid the club’s other risqué entertainments. A new character is introduced through these outings, that being Sally’s friend Fritz, who is eager to receive English lessons from Brian. They quickly become good acquaintances.

Between performances, Sally and Brian grow closer, sharing moments that reveal more about their lives to each other and to the audience. Brian is making somewhat of a steady income with English lessons, and Herr Ludwig returns with a paid translation job. A brief flirtation between Brian and Sally is suggested during this segment, largely at Sally’s initiative, though they quickly consolidate their relationship as strictly platonic. Brian does not seem predisposed to romantic interest in women, but this is Berlin, not London. Freedom and tolerance reign! Surely nothing will threaten that in the near future…

Signs of seismic change appear increasingly, but so far unnoticed or ignored by the main characters. The film subtly underscores the political shift with hammer-and-sickle graffiti, Nazi flags, and propaganda posters scattered throughout the backgrounds as their relationship develops.

While the Emcee playfully performs a Slapdance comedy onstage, a group of Nazis in civilian clothes arrive to avenge the boy expelled earlier, mirroring the Emcee’s comedic violence with a brutal beating to the club’s manager Max. This moment layers real violence and political unrest beneath the Kit Kat Klub’s entertainment. Whereas the characters don’t acknowledge the attack, the screenplay ensures the audience cannot look away.

BREAK INTO TWO

The Break into Two introduces Fraulein Natalia Landauer, Brian’s newest English pupil and, as Fritz informs him, a wealthy Jewish heiress. She is Sally’s foil – refined, poised, and raised in privilege. Fritz, initially motivated by gold-digging, becomes instantly smitten, and it quickly transpires that his attraction to Natalia extends beyond her wealth to her beauty and intelligence.

The screenplay makes a habit of introducing new characters at major junctures – inciting incident, break into two, and as we soon see – the midpoint.

FUN AND GAMES

Act Two tracks Natalia joining Fritz, Sally, and Brian as a quartet. Fritz grows increasingly smitten with Natalia, as Sally and Brian watch his courtship attempts, offering opinions as he struggles to woo her, though she remains indifferent. Meanwhile, Natalia is repeatedly taken aback by the behaviors of her less-privileged companions, particularly Sally.

Aside from Natalia’s introduction, much of the act is focused on Sally. In the screenplay, we meet her father, Mr. Bowles – a scene cut from the film, leaving him an offscreen presence. Sally’s fraught relationship with Mr. Bowles and her repeated, often futile efforts to earn his love and attention take centre stage. Understanding this dynamic deepens our sympathy for her, and casts her carefully cultivated, abrasive, enigmatic, yet performative charm in a more poignant light.

As the act progresses, more emphasis is assigned to romance. Fritz continues his attempts to court Natalia, while the romantic spark between Brian and Sally is fanned, revealing that the scope of Brian’s affections are not as rigid as he once believed. Their relationship remains strong as they pursue this new aspect, marked by hopefulness. On the Kit Kat Klub stage, Sally performs a personal, emotional number, “Maybe This Time,” singing of the hope that her bond with Brian might finally be genuine and enduring.

This act also delves more into Sally’s complicated relationship with her father, but many of the scenes developing this are cut from the final film. The film compensates for cutting Sally’s father scenes by advancing the Fritz–Natalia storyline. Following Sally’s advice, Fritz “pounces” on Natalia – on her father’s sofa, no less – a move that, improbably, succeeds. Natalia experiences genuine passion, more intense than anything in her sheltered life. But love alone cannot resolve their obstacles: she is wealthy and Jewish, and her father would never approve a marriage to a Christian man, especially one he might suspect is after her fortune.

MIDPONT

The midpoint introduces another new key character: Baron Lothar von Heune und Regensburg (shortened to Lothar). His entrance evokes the audacious thrill of a classic American romantic drama set in Europe.

Clearly a wealthy playboy, he and his status immediately charm Sally, suggesting that a man of his means could effortlessly open doors to opportunity and social prestige.

BAD TO WORSE

Brian is far from pleased by this development. Sally insists she’s only pursuing Lothar’s wealth to benefit them both, but Brian fears the Baron may come between them. His concern proves justified: Sally clearly enjoys Lothar’s attention, and Brian soon realizes the Baron is subtly attempting to seduce him as well, even while openly courting Sally.

Despite Brian’s resistance, Lothar’s charm succeeds on both fronts. He lavishes them with gifts; crystal glasses, a phonograph, fresh flowers filling Sally’s room, tailored shirts for Brian, and the fur coat Sally quickly adores. He even promises extravagant experiences, including an exotic trip to Africa for all three, financed entirely by him. In the glow of such wealth, the world’s troubles briefly fade from view.

At this point, the Fritz–Natalia storyline resurfaces after a period of absence. The film relocates and sanitizes Natalia’s confession about Fritz’s assault, reframing it as mutual attraction and a question of love versus tradition and her father’s approval. In the original screenplay, the scene is far less romanticized, carrying greater moral weight.

In the screenplay, Natalia comes to Sally’s home and confides what happened after Fritz followed Sally’s ill-advised counsel. She is visibly shaken and uncertain about how to proceed, questioning whether marriage is now expected after their sexual encounter. Complicating matters are her Jewish identity, Fritz’s Christianity, and her lingering sense that something is fundamentally “wrong” with him. This version is darker and more plausible, aligning more closely with the shifting tone of the third act.

Fritz later confides in Brian with alarming news: Natalia’s father has received antisemitic threats demanding the family leave Germany or face death. In response, Fritz admits he has concealed his own Jewish identity, a secret he has kept since arriving in Berlin—even from Natalia. While this deception shields him from immediate danger, it further alienates him from her.

Act three adopts a markedly darker tone as the proliferating Nazi influence becomes much harder to ignore. While Lothar drives Sally and Brian through the city, they witness a communist rally devolve into violence when men in civilian clothes, marked by Nazi armbands, overtake the protest. Amid the chaos, Lothar offers a chillingly pragmatic remark: Hitler may at least be useful in driving out the Bolsheviks.

Brian, Sally, and Lothar picnic in the park on a bright afternoon as a young man sings a cheerful patriotic tune. The camera pulls back to reveal his Nazi uniform, and surrounding civilians rise to join him in an eerie chorus. Sally and Brian try to ignore the moment, reassured by Lothar’s promises of escape. His wealth, they assume, will insulate them from political violence and the creeping rise of fascism.

BREAK INTO THREE

Unsurprisingly, the “rich playboy” lives up to his title – slipping out of Berlin without a word aside from a short note, leaving only his gifts and 300 marks behind. Reality crashes in. Sally and Brian fight; Brian storms off and provokes the Nazi magazine vendor, getting himself beaten bloody.

Sally then reveals she is pregnant, uncertain whether the child is Brian’s or Lothar’s. She doubts her ability to be a mother, yet an abortion is prohibitively expensive. Brian, clinging to optimism, reframes the crisis as a fresh start: marriage, America, money from his aunt, a teaching job. Somehow, they convince themselves it will all work out.

FINALE

Natalia and her family remain targets, rendering any future with Fritz impossible under rising antisemitism. Sally, meanwhile, refuses to abandon her dreams for motherhood. She understands herself too well – drawn to excitement, committed to the fantasy of stardom, incapable of permanence. She knows Brian will not stay forever, and that a child would only hasten their separation.

Ultimately, Sally sells her fur coat to pay for an abortion, acting without Brian’s consent because she knows he would object. Despite Berlin’s dangers, she chooses not to wake from its illusion, clinging to the corrupted glamour of the Kit Kat Klub. Brian understands but cannot remain. They love each other, yet their lives demand opposite paths.

As Brian returns to the train station, Sally takes the Kit Kat Klub stage for her final number. She articulates the philosophy that has guided her choice: why be burdened by personal loss or impending prophecy of political doom when the lights are bright and the music still plays? What claim does looming catastrophe have on her, here and now, amid pleasure and performance? Escape, she suggests, is preferable to a reality she cannot change. What other choice remains?

Sally sings of an old friend, Elsie – earlier mentioned as a fleeting trace of her past – who lived recklessly and died amid drugs and liquor, smiling to the end. Life, Sally insists, is only a cabaret, so why look beyond it? As she sings, the film cuts to Brian boarding his train, passing two uniformed Nazis. Under his breath, he begins the song the Emcee once used to welcome us in.

CLOSING IMAGE

The Emcee’s voice overlays Brian’s, returning us to the club. He asks where our troubles have gone – lost beneath Kit Kat Klub’s dazzling entertainment? They should be, he insists, for here lies a haven from the harsh outside world. As Sally finishes her song, reminiscent of the show’s opening, the audience now carries a somber air. Among the businessmen, patrons, and their wives, brown uniforms and swastika armbands are scattered—a quiet reminder that escape is fleeting.

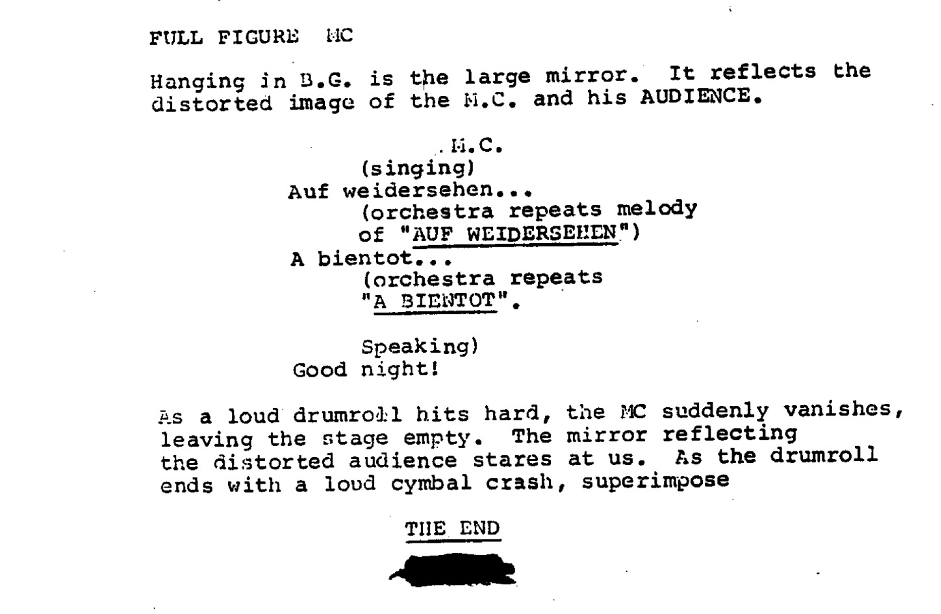

The music fades, the emcee bids us goodbye, ‘till next time, and goodnight, and we are left once again staring at the distorted mirror on the back of the stage, as the distorted faces of the audience stare back at us.

CONCLUSION

Overall, this adaptation honors Cabaret’s themes and warnings and tells its story competently. Its main flaw, however, is an overabundance of plotlines. At least two could have supported entire films on their own, but combined here, they dilute the impact of the story as a whole.

Cabaret juggles numerous characters, often forcing their relevance and creating loosely connected plotlines that could be streamlined without losing thematic impact. As a result, we fail to form deep connections with many figures. Characters introduced mainly to serve a function (Natalia, Lothar, Fraulein Kost, Fraulein Schneider) read as shallow or underdeveloped, which undermines the narrative; a show like Cabaret demands that its audience believe its people are real.

One-dimensional major characters are always a problem, and in Cabaret only Sally and Brian feel fully actualized – the supporting cast act as props. The Broadway musical handles this more effectively with a smaller cast. For example, it eliminates Lothar and reworks the “comfort of money” plotline around Herr Ludwig, who hires Sally and Brian to smuggle items for his political cause. This plot not only strengthens the narrative but also highlights the tension between friendship and extremist ideology, showing where moral lines are drawn.

The Nazis were not just faceless men in brown uniforms – they were everyday people, many of whom did not renounce the party despite its horrific beliefs as they were bound by personal ties. The Broadway musical also replaces Natalia and Fritz’s plot with a tighter, more effective story around Fraulein Schneider and an older Jewish man, Herr Schultz. It still explores doomed marriages and broken lovers, but does so with characters already integral to the audience’s emotional world.

The Kit Kat Klub is majorly underutilized for much of the screenplay. It appears mostly through songs, or as a convenient meeting place, serving mainly as a metaphor for the developments in Sally and Brian’s lives. Amid numerous tangential subplots, the club’s presence is almost forgotten. For the story to fully work, it must function as both a real setting and a symbolic reflection of Germany – never just one or the other.

Does Cabaret (1972) have its strengths? Certainly. Does it have major flaws? Yes. Is it the best way to experience the story? No – that, in my view, would be the 1993 Donmar Warehouse revival with Jane Horrocks and Alan Cumming. Still, these are just two of countless interpretations. With so many creative productions, artistic choices, and varied endings, there is no single “true” Cabaret. And I, for one, hope this story continues to be revived, reimagined, and celebrated for decades to come.

We award Cabaret (1972) a 3.5/5.